Spring burndown applications are an important part of field preparation, especially in no-till cropping situations. Such applications typically include glyphosate for grass control, along with dicamba and/or 2,4-D for broadleaf weed control, and a residual herbicide such as atrazine, metribuzin, or flumioxazin. Most years, this herbicide combination will result in effective weed control and a clean seedbed at planting time. However, this year, there have been several reports of poor control of grasses, especially weedy bromes and winter cereals following glyphosate applications that were made during the month of April (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An example of volunteer cereal rye not controlled by a herbicide application that included glyphosate plus dicamba. Photo by Sarah Lancaster, K-State Research and Extension.

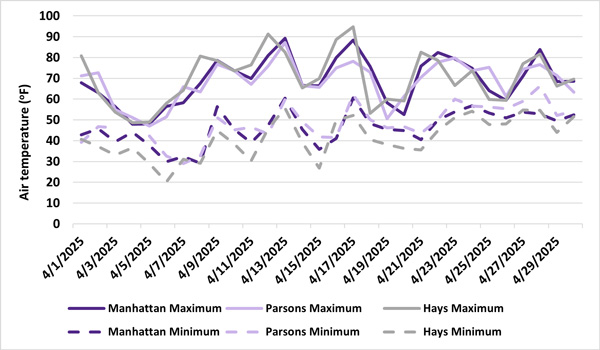

Figure 2. Daily maximum temperature and minimum temperature for the month of April 2025, recorded by the Kansas Mesonet stations at Manhattan, Parsons, and Hays, KS. Source: Kansas Mesonet.

Cool weather has been identified as the most likely cause of poor control in the situations we have discussed with farmers, applicators, and agronomists. Because active growth is required for maximum herbicide activity, consistently warm temperatures are necessary for optimal herbicide activity. In a recently published article, Chris Landau analyzed data from 14 states (including Kansas) and the province of Ontario to identify the characteristics of “successful” postemergence herbicide applications. The most important factors for a successful glyphosate application were temperature and precipitation during the 10 days before and after application. For large foxtail control by glyphosate, temperatures after application were the most important factor, with an optimum range of 66 to 77°F. Interestingly, cool temperatures (< 60°F) following application had a greater negative effect on giant foxtail control by glyphosate compared to other herbicide/weed combinations evaluated.

While the research mentioned above analyzed control of a summer annual grass, it is reasonable to apply this logic to the current challenges observed in controlling winter annual grasses, even though the base temperature for growth is less in winter annuals (32°F vs 50°F). For example, wild oat control by glyphosate was greater at 86°F compared to 68 or 77°F in greenhouse research. In many locations across the state, there have been few opportunities to make burndown applications with ideal temperatures. For example, at Manhattan, Parsons, and Hays, the longest span of days with temperatures above 60°F was 12 days from April 7 to April 18 at Parsons (Figure 2).

Other factors that may have contributed to the reduced control in the cases we are aware of include antagonism between glyphosate and tankmix partners such as dicamba and 2,4-D, lower (but still labeled) glyphosate rates, and lower rates of ammonium sulfate (AMS). Under ideal conditions, the tankmixes used would have likely provided acceptable weed control.

Sarah Lancaster, Extension Weed Science Specialist

slancaster@ksu.edu

Jeremie Kouame, Weed Scientist – Agricultural Research Center, Hays

jkouame@ksu.edu

Tags: weed control weather glyphosate herbicide application burndown herbicides