In last week’s eUpdate, we featured an article on field bindweed focusing on its ecology, growth characteristics, and identification methods. This week, the focus is on developing effective long-term control strategies for this troublesome weed that impacts Kansas farmers.

Because field bindweed has long seed viability and tremendous food reserves stored in roots, a long-term management program is required for successful control. A single herbicide application will not eradicate established stands; instead, multiple chemical and/or mechanical control means are needed to control and keep it suppressed. An effective long-term control program should prevent seed production, kill roots and root buds, and prevent infestation by seedlings. A good control program will include cultivation, herbicide use, and competitive crops.

Prevention

Because field bindweed can be spread by seed, root fragments, farm implements, infested soil, and animals, prevention of infestations is critical and requires:

- careful inspection of crop seeds to remove field bindweed seeds.

- confinement or restriction of livestock fed contaminated grain or hay to areas already infested until the bindweed seed passes through the animals.

- spreading of manure contaminated with field bindweed only on bindweed-infested land.

- thoroughly cleaning harvesting, tillage, and other machinery before moving from infested to non-infested fields.

- immediate control of new infestations that start in crop and non-crop areas.

- clean field borders from field bindweed infestation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Clean field borders are needed to prevent field infestations from lateral roots. Photo by Jeremie Kouame, K-State Research and Extension.

Competitive crops and early canopy closure as a management tool

Field bindweed requires high amounts of light. It cannot tolerate shading from tall competitive crops and is found primarily in crops with lower plant densities or with low leaf area indexes. Its presence and invasiveness are much lower in dense and healthy crops. Planting forage sorghum or sudangrass in narrow rows around mid-June, following intensive tillage, or using a herbicide provides excellent competitors in areas where adequate soil moisture enhances rapid crop growth1. Even though grain sorghum is usually less effective than taller forage crops, narrow-row grain sorghum can also be used as a competitive crop.

Chemical control

Several herbicides help manage field bindweed even though a single herbicide application rarely eradicates established stands. Instead, multiple herbicide applications will generally be needed to reduce and suppress dense stands over several years. Because of its deep rooting system and perennial nature, long-term chemical control depends on movement through the root system to kill the roots and root buds.

The systemic herbicides most commonly used are glyphosate (Roundup or equivalent), auxin-type herbicides 2,4-D, dicamba (Banvel/Clarity), picloram (Tordon), and quinclorac, and their mixtures. Research in a winter wheat-fallow rotation with treatments applied in late summer or fall each year for two, three, or four consecutive years at the beginning and end of each fallow period showed that quinclorac + 2,4-D and picloram + 2,4-D consistently performed better when applied during the fallow period2. Other studies in a winter wheat-fallow system showed that about one year after application, herbicide mixtures containing picloram provided the best control3. Using contact herbicides such as paraquat will only desiccate plant tissue contacted by the herbicide, resulting in short-term control of top growth. Control may be improved by combining herbicide treatments with closely-drilled, vigorously growing crops.

Seedling control

Because seedlings develop a deep taproot and numerous lateral roots about six weeks after emergence and six-week-old seedlings can re-establish under favorable conditions following top growth removal, it is advisable to control seedlings before this stage. Also, seedlings can be:

- easily controlled with timely tillage for the ones emerging between crop rows,

- controlled with applications of 2,4-D or dicamba at 0.25 to 0.5 lb ai/acre in herbicide-tolerant crops, and

- removed by hand when they are growing within rows to prevent their establishment as perennial plants.

Tillage

Tillage is a common way to destroy top growth and is most effective when sweep-type implements are used to cut shoots from the roots approximately 4 inches below the soil surface. In the Great Plains, the standard practice for control is sweep tillage at 3-week intervals combined with one or two annual 2,4-D applications during the 14-month fallow period in a winter wheat-fallow crop rotation4. If tillage occurs every 12 to 16 days after bindweed emerges, between harvest and seeding, a relatively good continuous wheat stand can be produced under favorable soil moisture conditions, significantly reducing field bindweed stands. This repeated destruction of the plant every 12 to 16 days weakens the plants by depleting carbohydrate reserves in the roots and stimulating dormant bindweed seeds to germinate.

Chemical control improved when vigorous plants are sprayed but is affected by tillage timing

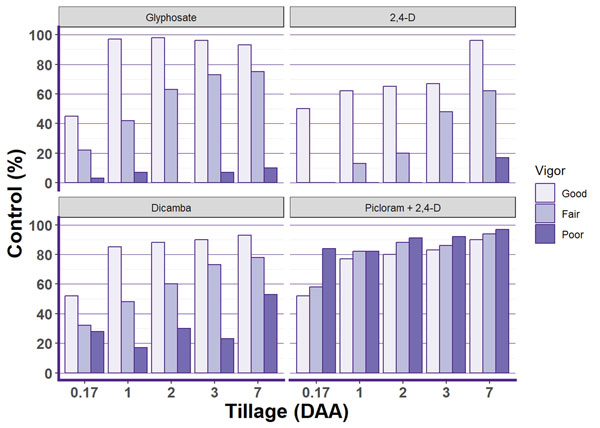

Field bindweed control 10 months after application of glyphosate (3 lb/acre), 2,4-D (1 lb/acre), dicamba (1 lb/acre), or picloram + 2,4-D (0.25 + 0.5 lb/acre) is affected by the time of sweep tillage (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Field bindweed control as affected by sweep tillage at various times [0.17 (or 4 hours), 1, 2, 3, 7 days after herbicide application (DAA)] to plants with good, fair, or poor vigor, respectively (Graph created using data from Wiese et al., 1997)5.

- Glyphosate provided excellent control (93 - 97%) of plants with good vigor if tillage was delayed 1 DAA, but the maximum control achieved for plants with fair vigor was about 75% when sweep tillage was delayed at least 3 DAA. Only minimal control was achieved for plants with poor vigor, regardless of tillage time.

- 2,4-D provided excellent control (96%) of plants with good vigor when tillage was delayed 7 DAA but the maximum control of plants with fair vigor was 62%, when tillage was delayed 7 DAA. Little or no control of bindweed was achieved when 2,4-D was applied to poor vigor plants, even when tillage was delayed 7 DAA (17%).

- Dicamba provided good control (90 - 93%) of plants with good vigor when tillage was implemented 3 DAA but the highest control achieved for plants with fair vigor was 78% when tillage was delayed 7 DAA. Only 23% control was achieved for plants with poor vigor when tillage was delayed 3 DAA and reached 53% when tillage was implemented 7 DAA.

- Picloram + 2,4-D. Field bindweed vigor at the time of application had little effect on control. If tillage was delayed for at least 2 days after application, it did not affect control, which was 80 - 97% regardless of plant vigor. This mixture was the only herbicide program that provided control between 82 and 97% of poor vigor-rated plants regardless of tillage timing.

Fallow preceding wheat: tillage or a herbicide application immediately after harvest could reduce seed production, weaken the plant, and increase the effectiveness of follow-up herbicide applications in the fall or spring. picloram + 2,4-D at 0.25 + 0.5 lb/A should be applied at least 60 days prior to seeding winter wheat.

A preharvest application of 2,4-D ester can be used in wheat, oats, and barley crops after small grains have reached the soft dough stage.

Postemergence to corn and grain sorghum. Dicamba and 2,4-D may be applied but crop tolerance varies depending on hybrid, environmental conditions and growth stage at the time of application. Always check the relative tolerance of particular hybrids to herbicides prior to use.

References

1Peterson and Stahlman, 1989, 2Enloe et al., 1999, 3Westra et al., 1992, 4Wiese et al., 1996, 5Wiese et al., 1997

For more detailed information, see the “2024 Chemical Weed Control for Field Crops, Pastures, and Noncropland” guide at https://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/CHEMWEEDGUIDE.pdf or check with your local K-State Research and Extension office for a paper copy.

The use of trade names is for clarity to readers and does not imply endorsement of a particular product, nor does exclusion imply non-approval. Always consult the herbicide label for the most current use requirements and follow all label instructions.

Jeremie Kouame, Weed Scientist, Agricultural Research Center – Hays

jkouame@ksu.edu

Sarah Lancaster, Weed Management Specialist

slancaster@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Southeast Area Agronomist – Garden City

lsimon@ksu.edu

Patrick Geier, Assistant Weed Scientist, Southwest Research & Extension Center

pgeier@ksu.edu