Highlights

- A wet January will transition to a drier late February and March.

- South central to northwest Kansas have above-normal grass loading from 2020.

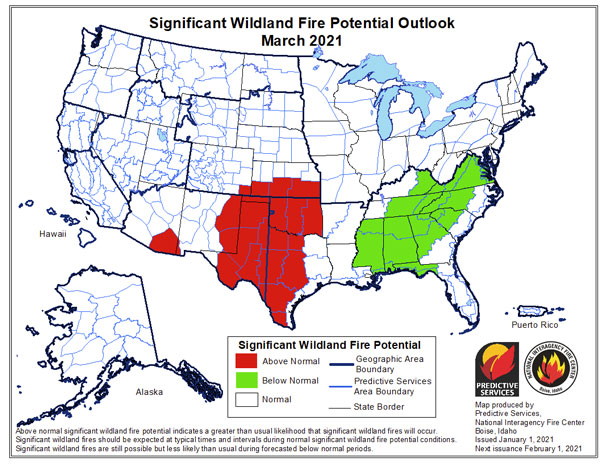

- Expect an increase in wildfire potential with a large fire concern from dry frontal passages and growing drought into April.

- Kansas fire season (Feb - Apr) is expected to be slightly above average with an increase in large fires than observed the last two spring seasons.

Change is coming

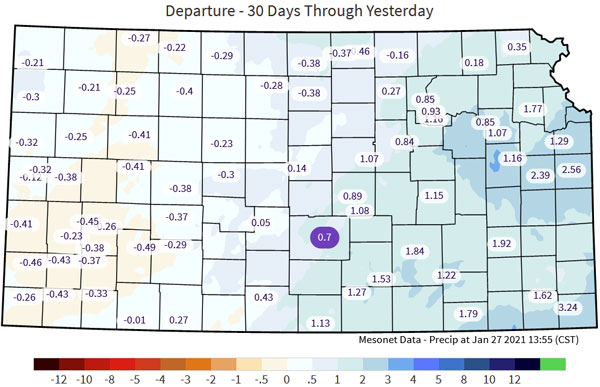

Despite a wet January thus far for a majority of Kansas (Figure 1), that doesn’t exactly imply what is in the future. January typically averages the least amount of precipitation of any month. Therefore, it is easy for one or two storms to skew statistics. While there is also snow on the ground across much of the state as of this writing, the moisture content of the snow is rather low and will translate into only a few tenths of an inch when melted. Currently, forecasts after the first full week of February are suggesting a large pattern change will occur into March. This pattern will be more La Niña-like and conducive to dry frontal passages. In addition, precipitation trends are expected to swing below normal through most of spring, a time of more critical importance for annual moisture totals.

Figure 1. 30-day departure from normal precipitation. Data available here: mesonet.ksu.edu/precip/daily

Poor timing

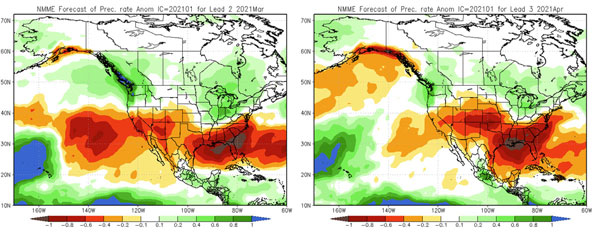

The pattern transition to warmer and drier with increased frontal passages will coincide with what we typically consider the fire season in Kansas. An increase of fronts typically results in an uptick of Kansas wind events. Most historically large fires (and mega-fires) in the state have occurred with strong frontal systems. In combination with a higher-than-normal fuel load (which has already resulted in a few large fires this winter), this is likely to increase fire concerns through March. Another concern is the current ongoing drought in much of western Kansas. Recent moisture has not offset the current drought and has had little impact on heavier fuel models (timber, cedar, etc.). With forecast models still suggesting drier-than-normal conditions through the spring (Figure 2), these conditions are expected to expand eastward once again.

Figure 2. Precipitation rate anomalies for March (left) and April (right) via NOAA NMME (https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/NMME/monanom.shtml).

Ending fire season

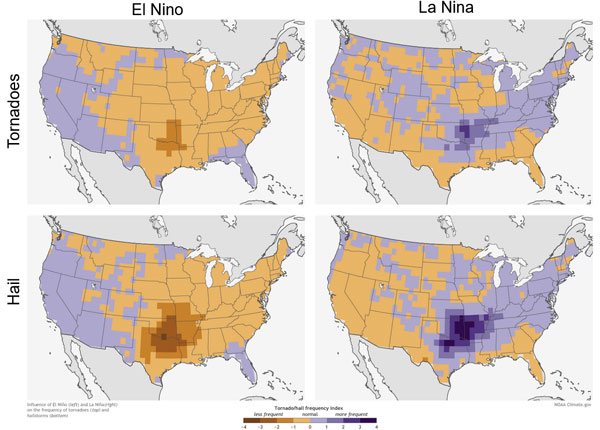

The duration of fire season is typically dictated by several factors consisting of precipitation, temperature, time of the year, and less wind events. This past year, the fire season never really stopped, with large fires reported every month during the winter. Spring, a time of transition between winter and summer, can almost guarantee strong frontal systems and (usually) the windiest time of the year. We usually focus on precipitation events enhancing grass green-up and preventing fire starts. It may seem promising that in La Niña, there is typically an increase in severe weather with both hail and tornadoes (Figure 3). While an increase in moisture usually occurs with severe weather - it also represents the strength of storm systems. A stronger storm system suggests increased wind potential and resulting wildfire potential enhanced to the west of the thunderstorms. Precipitation timing is critical and if consecutive storm systems can impact the region with widespread moisture mid-to-late March, it could drastically enhance green-up and aid in diminishing wildfire concerns. However, predicting that type of system this far in advance is a challenge. Currently, we are focusing on the increased potential of wind, dry conditions and warmer-than-normal temperatures that will result in increased wildfire potential (Figure 4). It is very likely that these conditions will occur before consecutive wetting rains can occur with green-up and time of the year (late March to early April).

Figure 3. Frequency of tornadoes (top) and hail (bottom) during El Niño (left) and La Niña (right) via NOAA (https://www.climate.gov/news-features/featured-images/el-ni%C3%B1o-and-la-ni%C3%B1a-affect-spring-tornadoes-and-hailstorms).

Figure 4. Significant wildland fire potential outlook from National Interagency Fire Center Predictive Services (https://www.predictiveservices.nifc.gov/outlooks).

Christopher “Chip” Redmond - Kansas Mesonet

christopherredmond@ksu.edu

Mary Knapp - Weather Data Library

mknapp@ksu.edu

Eric Ward - Kansas Forest Service

eward@ksu.edu