A Brief History

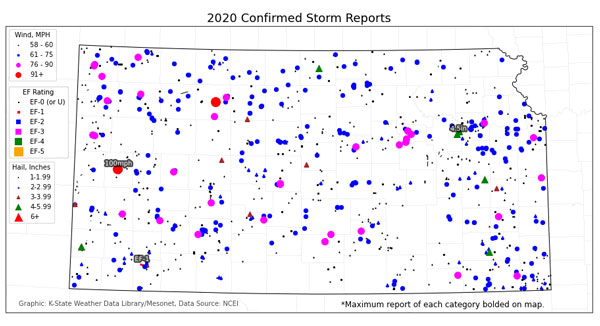

Severe weather record accuracy and dependency are limited by history. Good records didn’t get established until the early 1990s. As a result, data records prior are limited and not likely representative of increased severity. In addition, the increase in population and storm spotters have exponentially increased over the decades with a subsequent increase in severe weather reporting. With 2020 completed (Figure 1), there are now 30 years where data has increased confidence in accuracy and reliability. Therefore, we use the period 1991-2020 for the historical comparison.

Figure 1. All confirmed severe weather reports as of January 4, 2021 from the 2020 calendar year. Source: K-State Weather Data Library/Mesonet.

Negligible Tornadoes

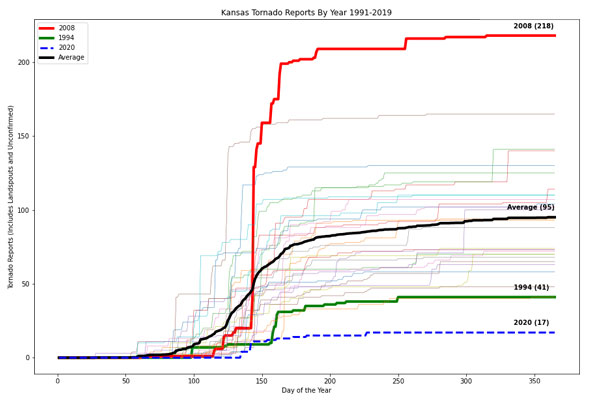

Probably the biggest headline this year is the lack of tornadoes in 2020. On average, Kansas sees 95 tornadoes a year from 1991-2020 (Figure 2). The year with the highest tornado count was 2008 with an incredible 218 reports from several outbreaks. The quietest years since 1991 were 1994 and 2014 with only 41 and 43 respectively. This year, those quietest years were bested by just 17 total tornadoes reported in Kansas, less than half of the previous low.

Figure 2. Tornado accumulation by day of the year, by year. Average tornadoes are delineated by a black line, year with the highest (2008) and lowest (1994) ending tornadoes are highlighted. 2020 is a dotted blue line with a new record low ending tornado count for Kansas.

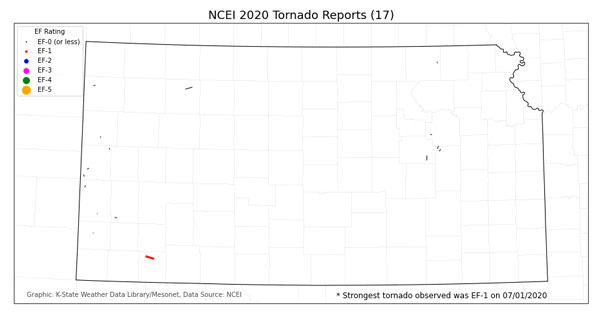

Of those 17, only one was rated an EF-1 while the others were either EF-0 or EF-U, most occurring in unpopulated areas (Figure 3). That EF-1 also occurred in July, outside the typical April - June tornado season. Another remarkable point was the lack of tornadoes in the central portion of the state. This year, the Wichita National Weather Service forecast office never issued a tornado watch nor received a tornado for the first time ever. Previously, the latest in the year the south-central region recorded a tornado was August. This year obviously broke that record with none all year.

Figure 3. 2020 confirmed tornadoes via NCEI.

There are many factors that contribute to episodes of tornadoes in the spring. Of which, many are discussed by the Wichita National Weather Service here: https://twitter.com/NWSWichita/status/1338660982298615810.

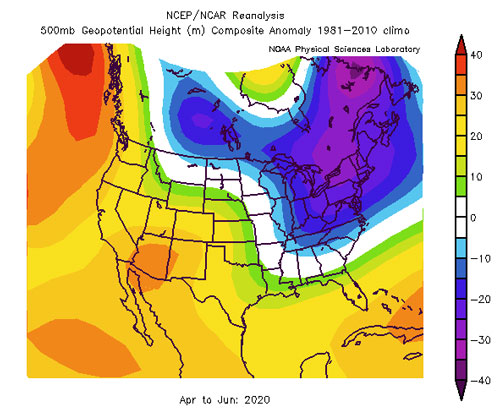

In addition to persistent northerly winds, lower moisture and instability, the higher than normal geopotential heights along the west coast implied more ridging (or high pressure) along the West Coast during our typical prominent spring storm season. These higher pressures (warmer colors along the West Coast in Figure 4) to our west often kept the northwest flow across Kansas and helped account for warmer/drier conditions to our west. These implications expanded beyond tornadoes in the Plains but also were a significant contributor to the growing intense drought being observed by much of the West Intermountain region.

Figure 4. Geopotential height anomalies in April - June 2020 compared to climatology. Warmer colors imply high pressure while cooler colors imply lower pressure than normal (NCEP).

Hail Occurrences

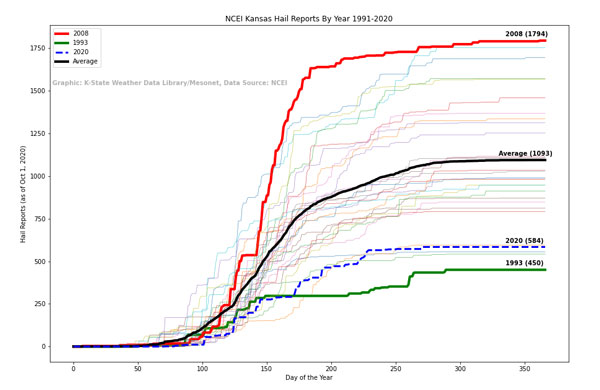

Not only were tornado occurrences down in 2020, but all forms of severe weather saw a dramatic decline from average levels. Hail reports weren’t at new record lows for the climate period, but were still much below average. While 584 hail reports may sound like a lot, when totaled over the entire year, it is actually only about half of the average (severe) hail reports Kansas typically observes per year, 1093 (Figure 5). Keep in mind, this only considers severe hail (1.00” or greater). Before 2010, hail of 0.75” or greater were considered severe and thus, prior years may have more reports of what we currently consider non-severe in 2020. These numbers have not been adjusted to consider this change.

Figure 5. Hail accumulations by day over the course of a year in 2020 (dashed blue line) compared to the last 30 years. The maximum (2008) is denoted by a red line, minimum (1993) by green, and the 30-year average by a black line.

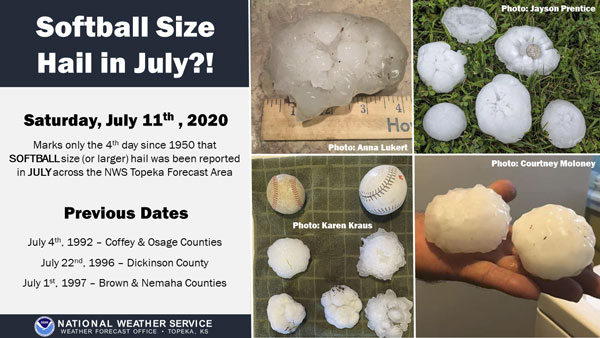

There were still several peak severe weather days in 2020, just fewer than typical. The day with the greatest amount of hail reports was May 4 with 72 occurring in the eastern part of the state. Also, the largest hailstone observed was 4.5” on July 11, 2020 in eastern Wabaunsee County (Figure 6). This is a rarity for July in northeast Kansas and only the fourth time hail this large has been reported in the month for the area. Typically, the mid-levels of the atmosphere are too warm to support large hail. Cold mid-levels support the growth of hail and are required with strong instability for significant hail stones.

Figure 6. National Weather Service graphic of the large hailstones that fell on July 11, 2020 and historical precedence for northeast Kansas large hail in July (Source: Twitter).

Wind Occurrences

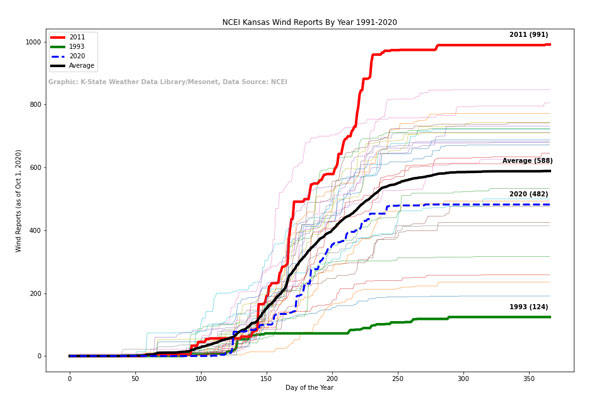

With low amounts of tornadoes and hail, it is no surprise that wind reports were also below average (Figure 7). However, wind reports were closer to normal than the other severe weather parameters. On average, Kansas observes 588 reports of severe wind over the last 30 years. Note, we are only considering thunderstorm driven wind reports that are measured at the severe level, 58mph or greater. In 2020, Kansas observed 482 severe wind reports. The largest event was May 4 with 51 reports of strong wind. The strongest wind reported in 2020 was a gust to 100mph near Leoti. This gust strength was estimated from damaged power poles in the area.

Figure 7. Wind report accumulations by day over the course of a year in 2020 (dashed blue line) compared to the last 30 years. The maximum (2011) is denoted by a red line, minimum (1993) by green, and the 30-year average by a black line.

Implications for 2021

A question people often get after a slow severe weather year is “what does this mean for the upcoming severe weather season?” Unfortunately, there are no implications from year to year. With a moderate La Niña in this winter, there is often an increased probability of spring severe weather. In addition, any “average” activity would seem substantially more than the quiet 2020 season. With that in mind - now is the time to start preparing for Kansas severe weather. For guidance on preparation see here: https://www.ready.gov/severe-weather.

Summary

- Lowest amount (17) of yearly tornadoes observed in Kansas history.

- Hail and wind were both below the 30-year average; hail much below.

- The largest severe weather event occurred on May 4th with 72 hail and 51 wind reports.

- A quiet severe weather season is rarely a precursor to a significant season the following year.

Christopher “Chip” Redmond - Weather Data Library Manager

christopherredmond@ksu.edu

Mary Knapp - Assistant State Climatologist

mknapp@ksu.edu

Tags: severe weather