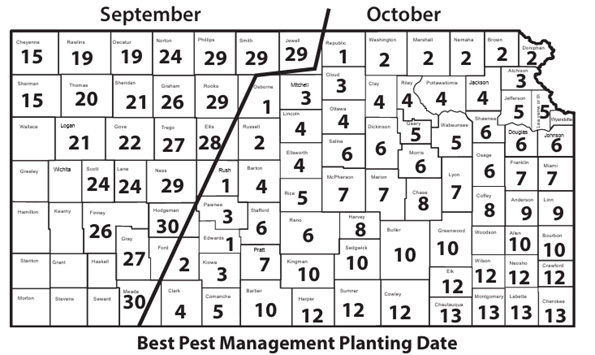

The general target date for planting wheat for optimum grain yields in Kansas is within a week of the best pest management planting date, or BPMP (formerly known as the “Hessian fly-free”) date (Figure 1). Planting after these dates not only benefits grain yield, but may help reduce the risk of serious pests and diseases that can damage the wheat crop in Kansas. If forage production is the primary goal, earlier planting (mid-September) can increase forage yield. However, if grain yield is the primary goal, then waiting until the BPMP date to start planting is the best approach (Figure 3). Planting in mid-September is ideal for dual-purpose wheat systems where forage yields need to be maximized while reducing the effects of early planting on reduced grain yields.

Figure 1. These dates were established several years ago. Although fields may still be infested with Hessian fly when planted after these dates if the weather is mild, later planting dates generally reduce problems from Hessian fly, aphids, wheat curl mites, and many diseases. Map from https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/wheat-insect-pest-management-2025_MF745.pdf.

Optimum wheat planting dates in Kansas depend on location within the state (Figure 2).

Zone 1: September 10-30

Zone 2: September 15 – October 20

Zone 3: September 25 – October 20

Zone 4: October 5 – 25

Figure 2. Optimum wheat planting dates by zone in Kansas.

Figure 3. Effect of planting date and seeding rate on wheat fall forage yield in Lahoma, north-central Oklahoma (a) and effect of planting date on wheat grain yield near Hutchinson, south-central Kansas (b). Figure adapted from KSRE numbered publication MF3375.

While planting date effects on wheat yield shown in Figure 3 are generally consistent, they depend heavily on environmental conditions and disease pressure during the growing season. In some years, earlier planting performs best; in others, later planting has the advantage, usually related to weather in the fall and spring. For instance, early-planted fields with a warm fall might produce excessive biomass that will use substantial water during the fall. If the following spring is dry, the soil water deficit during grain filling can reduce grain yield. Conversely, a warm fall would favor tillering of a later-planted wheat crop, helping to compensate for this delay. The opposite is also true: when cold temperatures arrive early, an earlier-planted crop might perform better than a later-planted crop due to its ability to produce enough fall tillers to still maximize grain yield.

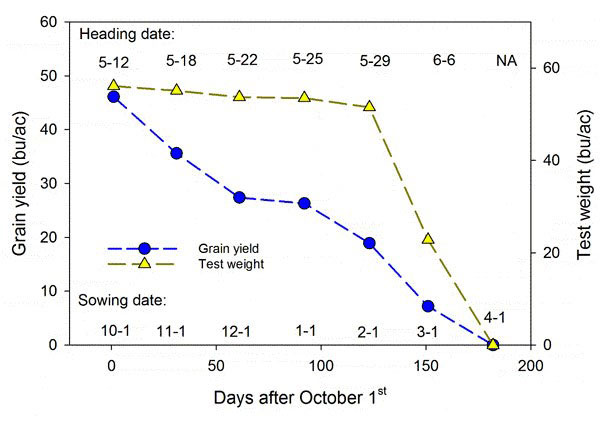

Research conducted by Merle Witt with late-sown wheat in Garden City from 1985 through 1991 is summarized in Figure 4. Averaged across all these years, delaying wheat sowing from October 1 to November 1 delayed the heading date by 6 days and decreased wheat yields by 23%. The grain-filling period was progressively shortened by about 1.7 days and occurred under hotter temperatures (about 1.5°F) for every month of delay in sowing date.

Figure 4. Wheat grain yield, test weight, and heading date responses to sowing date between 1985 to 1991. Data adapted from Kansas Agric. Exp. St. SRL 107.

In dry years, wheat may emerge unevenly, with poor crown root development and fall tillering. Conversely, if fields remain too wet past mid-October, planting is often delayed well beyond the optimum date. After such unusual years, producers may be tempted to plant earlier than recommended when soils are favorable, but early planting increases the risk of diseases, insect pests, weeds, and excessive fall growth.

Potential risks of planting wheat early

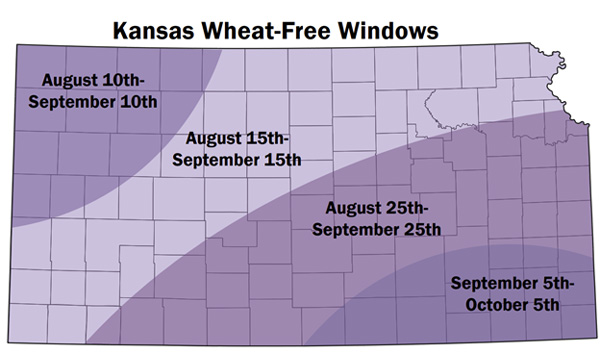

Increased risk of wheat streak mosaic complex. Wheat curl mites that spread these viruses survive the summer on volunteer wheat and certain other grasses. As those plants die off, the wheat curl mites leave in search of new plants to feed on. Early-planted wheat is likely to become infested and, thus, become infected with wheat streak mosaic virus, high plains wheat mosaic virus, and Triticum mosaic virus. The wheat curl mites are moved by wind and can be carried a mile or more before dying, so if wheat is planted early, make sure all volunteer wheat within a mile is completely dead prior to planting. This year, we are recommending avoiding planting wheat during regional “wheat-free windows” to lower the risk of mite-transmitted viruses (Figure 5).

For growers considering planting early, a good management consideration would be to select wheat varieties with resistance to the wheat streak mosaic virus and/or with tolerance to the wheat curl mite, especially in the western portions of the state. Updated disease and insect ratings for wheat varieties can be found here: (https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/item/kansas-wheat-variety-guide-2025_MF991).

Figure 5. Proposed wheat-free windows in different regions of Kansas to reduce the likelihood of a wheat streak mosaic complex outbreak during the subsequent season. Wheat-free windows are defined as the 30-day period prior to the start of the optimal winter wheat planting date for the region. Graphic by Kelsey Andersen Onofre, K-State Research and Extension.

Increased risk of Hessian fly. Over the summer, Hessian fly pupae live in the old crowns of wheat residue. After the first good soaking rain in late summer or early fall, these pupae (or “flaxseed”) will hatch out as adult Hessian flies and start looking for live wheat plants to lay eggs on. They are most likely to find either volunteer or early-planted wheat. After the BPMP date, many of the adult Hessian flies in a given area will have laid their eggs, so there is generally less risk of Hessian fly infestation for wheat planted after that date. Hessian fly adult activity has been noted through November or early December in Kansas. If planting early, consider varieties with improved tolerance to Hessian fly.

Armyworms and other lepidopteran larvae may also still pose a serious problem to early planted wheat. They may feed on the green wheat plants until the first cold front comes through (temperatures in the mid-20-degree F range for a couple of hours). Insecticide seed treatments do not work well against lepidoptera larvae.

Grasshopper populations typically decline in late summer and early fall, as females lay eggs in August and September and then die. By this time of year, many surviving grasshoppers are parasitized, sick, or otherwise less interested in feeding compared to earlier in the season. If treatment is needed, foliar applications can often be limited to field edges where grasshoppers are moving in, rather than applied broadly. In contrast, seed treatments are applied before planting, well before infestations can be assessed, and are rarely justified in Kansas.

Most wheat insect and mite pests can be effectively managed in the fall by planting as late as agronomically feasible in your area and destroying all volunteer wheat at least two weeks before planting.

Fall Armyworm/Armyworm Considerations in Volunteer Wheat

Because of the large armyworm and fall armyworm populations this year and in years past, some producers are considering adding insecticide to volunteer wheat herbicide applications to save on costs. However, this is not recommended. First, destroying volunteer wheat will starve larvae, push them into pupation, or expose them to predators. Second, insecticides should only be used when pests are at a vulnerable stage and above treatment thresholds. Finally, any insecticide applied now will lose activity long before planted wheat emerges. Control the volunteer wheat, but resist the urge to tank-mix insecticide.

Increased risk of barley yellow dwarf. There are over 20 species of aphids that use wheat as a host. Many types of aphids can spread barley yellow dwarf. In Kansas, greenbugs and bird cherry-oat aphids are the primary vectors of this viral disease. These insects are more likely to infest wheat during warm weather early in the fall than during cooler weather. Planting wheat after the BPMD reduces the risk of problems with aphids and barley yellow dwarf. If planting early, consider varieties with improved tolerance to Barley Yellow Dwarf virus, especially in central and eastern Kansas, or consider using seed treatments with imidacloprid (such as Gaucho XT or Rancona Crest). If using insecticide seed treatments for wheat pests, please remember: They are most effective for the first 30 days after planting, and they are not effective on mites or lepidopteran larvae, i.e., armyworms or army cutworms, etc.

Increased risk of excessive fall growth and fall tillering. For optimum grain yield and winter survival, wheat should enter winter with established crown roots and 3-5 tillers. Early-planted wheat can grow much more than this, especially if moisture, temperature, and nitrogen levels are not limited. Excessive fall biomass can deplete soil moisture through unproductive vegetative growth, increasing drought stress in spring and susceptibility to winter injury (Figure 6). The wheat on the left (showing white discoloration of the leaves) was planted in mid-September for dual-purpose use and had excessive fall growth, nearly 3,000 pounds of dry matter/acre. The wheat on the right was planted early to mid-October for grain-only and had much more limited fall biomass. The white discoloration of the high-biomass plots occurred after a late-winter/early-spring freeze that was more damaging to the dual-purpose crop. Notice the darker green plots in the upper left corner amid discolored plots: while these were planted early, their growth was cut back by simulated grazing.

Figure 6. Aerial photo of side-by-side wheat trials near Hutchinson, KS, during the 2021-22 growing season. Photo taken in March 2022 by Jorge Romero Soler.

Increased risk of take-all, dryland foot rot, and common root rot. Take-all is usually worse in early-planted wheat than in later-planted wheat. In addition, one of the ways to avoid dryland foot rot (Fusarium graminearum and other Fusarium species) is to avoid early seeding. This practice promotes large plants that more often become water-stressed in the fall, predisposing them to invasion by the fungi. Early wheat planting also favors common root rot because this gives the root rot fungi more time to invade and colonize root and crown tissue in the fall. Fungicide seed treatments are an option for early-season seedling diseases, although they only provide suppression for later infections. More information on seed treatments: https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF2955.pdf

Grassy weed infestations become more expensive to control. If cheatgrass, downy brome, Japanese brome, or annual rye come up before the wheat is planted, they can be controlled with glyphosate or tillage. If wheat is planted early and these grassy weeds emerge after the wheat, producers will have to use an appropriate grass herbicide to control them. If a field has a history of grassy weed problems, consider planting a Clearfield or CoAxium wheat variety.

Germination problems due to high soil temperatures. Early-planted wheat is sown in hotter soils, which may become problematic because some wheat varieties are sensitive to high temperatures during germination. In fact, some varieties will not germinate when soil temperatures are greater than 85°F. Additionally, some varieties can have their coleoptile length reduced by as much as 40% in hot compared to cool soils. If planting early, it is important to select varieties that do not have high-temperature germination sensitivity or sow sensitive varieties later in the fall when soil temperatures have cooled down.

Emergence problems due to shortened coleoptile length. Hotter soils tend to decrease the coleoptile length of the germinating wheat. Therefore, deeply planted wheat may not have long enough coleoptiles to break through the soil surface, resulting in decreased emergence and poor stand establishment. When soil temperatures are hot, it is often better to plant wheat at a shallower depth (3/4 to 1 inch deep), even if moisture is absent in the top layers of soil. Planting wheat deep (>2 inches) increases the risk of poor emergence and unacceptable stands.

Take-home message

Early planting of wheat can increase risks that affect stand establishment and yield:

- Disease risk: Greater chance of insect- or mite-transmitted viral diseases.

- Emergence challenges: High temperatures can reduce germination and shorten coleoptile length in some varieties.

- Optimal planting: Aim for the recommended planting window whenever possible.

- Variety selection: If planting early (due to moisture or dual-purpose systems), choose varieties tolerant to major regional yield-limiting factors.

- Seed treatments: Strongly consider fungicide and insecticide seed treatments when planting early in Kansas.

Romulo Lollato, Extension Wheat and Forages Specialist

lollato@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist, Southwest Research-Extension Center

jholman@ksu.edu

Kelsey Andersen Onofre, Extension Wheat Pathologist

andersenk@ksu.edu

Erick DeWolf, Wheat Pathologist

dewolf1@ksu.edu

Jeff Whitworth, Extension Entomologist

jwhitwor@ksu.edu

Sarah Lancaster, Extension Weed Science Specialist

slancaster@ksu.edu

Tags: wheat optimum planting dates wheat planting early-planted wheat