Nitrate is a common contaminant in groundwater. Groundwater with excessive nitrate contamination can have immediate and long-term health effects. Groundwater supplies about 50% of the drinking water in the United States. Almost all private water supplies are from wells or springs. This recently updated publication, Nitrates and Groundwater MF857, addresses the drinking water nitrate standard, water testing, nitrate sources, the reduction of nitrate contamination risk, and groundwater treatment methods.

Human Health Concerns for Nitrate

The immediate health concern is the conversion of nitrate to nitrite in the digestive tract by nitrate-reducing bacteria. Nitrite is readily absorbed into the blood where it combines with the hemoglobin that carries oxygen and forms methemoglobin, which cannot carry oxygen. The resulting reduced oxygen supply to the body tissues produces physical stress. In infants, this condition is called methemoglobinemia, or blue baby syndrome, because of the blue color around the eyes and mouth.

Infants, both human and animal, are the most susceptible to nitrate poisoning because bacteria that convert nitrate to nitrite are abundant in their digestive systems. By the time a child is 6 months old, the digestive system produces acid that prevents nitrate-reducing bacteria from thriving, and the risk is greatly reduced.

Animal Health and Nitrates

Animals respond similarly, but the digestive tract may mature more quickly. Older ruminant animals, such as sheep, cattle, and goats, have a different digestive system that allows nitrate-reducing bacteria to thrive. Horses have a large cecum where nitrate-reducing bacteria also thrive. High-nitrate effects on livestock include reduced conception rates, spontaneous abortions, reduced rate of gain, and poor performance in dairy cows, including reduced milk production.

Maximum Contaminant Level

The maximum contaminant level (MCL) for nitrate in drinking water is 10 ppm or 10 mg/L nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N). Long-term exposure at two to three times the MCL can produce an increase of methemoglobin, which may not show outwardly but causes stress that may be blamed on other causes. Pregnant women and people with health infirmities should be protected from high-nitrate sources. The long-term effect occurs when nitrate is more than twice the MCL.

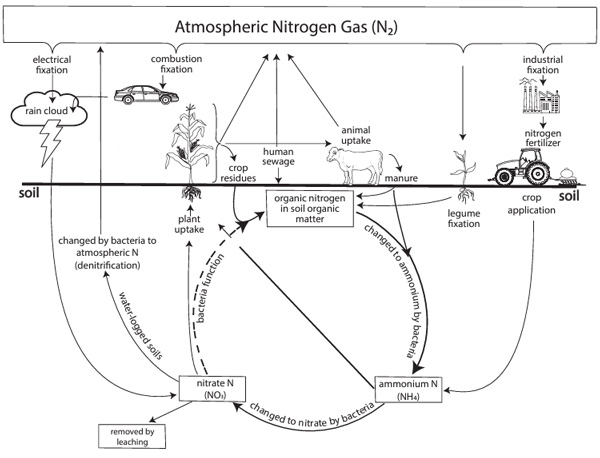

Nitrogen is lost from the soil by leaching, denitrification, volatilization, and immobilization (Figure 1). From the standpoint of groundwater quality, leaching is the only concern. The potential for nitrate leaching varies with soil type and rainfall or irrigation. Sandy soils under high rainfall or irrigation have high leaching potential. Fertilizer application beyond crop requirements and poor management of any nitrogen source can increase the potential for nitrate leaching.

Figure 1. The nitrogen cycle. The graphic was taken from KSRE publication MF857. It originated from Fertilizers and Soil Amendments, 1981. Prentice-Hall, Inc. and adapted with permission.

Summary

High nitrate levels in water are a health concern. Excess nitrogen can be converted to nitrate, moves with water, and may reach groundwater. Nonagricultural and agricultural sources of nitrogen contribute to the total nitrate levels. All nitrate sources require careful management to minimize the risk for contamination of groundwater and private wells. Careful management of livestock lots and use of the proper rate of nitrogen are the most important factors, but other management practices also are important. Recommended practices that minimize the risk of contamination should be given careful and immediate attention.

The full publication containing more information on management options and drinking water treatment is available at https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/nitrate-and-groundwater_MF857.pdf.

Stacie Minson, Extension Watershed Specialist, KCARE

sedgett@ksu.edu

Other contributors:

Pat Murphy, Extension Engineer, retired

Joe Harner, Extension Engineer, retired

Herschel George, Watershed Specialist, retired

Dan Wells, Environmental Administrator, KDHE

Melissa Harvey, KCARE

Tags: nitrate water quality KCARE groundwater