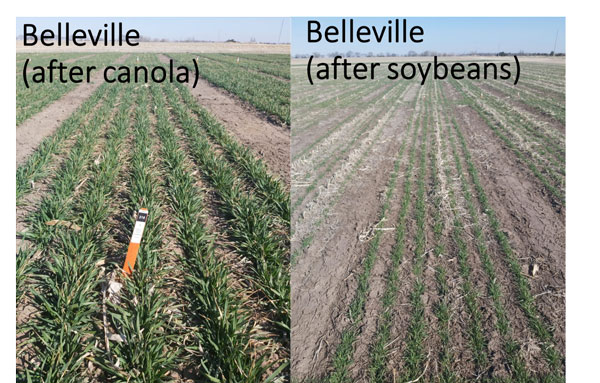

The crop conditions around Kansas are variable depending on region and planting date. Around the state, there was good precipitation around mid-September, so wheat that was planted up until the later part of September emerged on time and attained good stand establishment and early development. For the large majority, these would include wheat fields planted after a fallow period in western Kansas (about 57-66% of the crop in western Kansas), and wheat fields planted after wheat or after canola in central Kansas (about 32-49% of the crop in central Kansas) (Figure 1, 2, 3). For the most part, these fields emerged by the first week of October and were able to produce a good number of tillers, as well as good root development, improving its winterhardiness.

Figure 1. Wheat crop planted late-September after canola or early-October after soybeans in Belleville, North Central Kansas, during the 2020-21 season. Photos by Nicolas Giordano, graduate student in Agronomy.

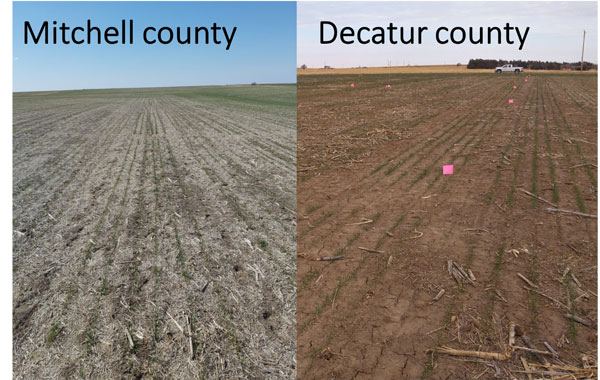

Wheat fields that were planted later, especially those after ~October 10th, had very limited moisture to ensure a timely emergence, owing to a very dry month of October and early November (Figure 4). These fields were usually planted after a preceding corn crop in western Kansas or after soybeans in central Kansas. Even if these fields were planted relatively on time (for example, mid-October in central Kansas), the emergence rate was considerably lower due to a lack of precipitation. Consequently, as much as 36% of the Kansas crop emerged as late as November, depending on the region of the state. These fields had a much more limited development in the fall both in terms of tillers and root, owing to a combination of a late emergence and cool and dry weather conditions.

Figure 2. Wheat crop planted mid-September after wheat or early-October after soybeans in Hutchinson, North Central Kansas, during the 2020-21 season. Photos by Luiz Pradella, visiting scientist, Agronomy.

Figure 3. Wheat crop planted late-September after a fallow period near Leoti, West-Central Kansas, during the 2020-21 season. Photo by Romulo Lollato, K-State Research and Extension.

Figure 4. Wheat planted mid- to late-October in Mitchell county (North Central Kansas) and Decatur county (Northwest Kansas) that did not emerge until November or December 2020.

Any winterkill from the mid-February arctic temperatures?

The lowest air temperatures in mid-February ranged from -11°F in south central Kansas to -29°F in north central Kansas, which is sufficiently cold to cause damage and/or winterkill to the wheat crop. Another factor increasing the chances of winterkill was the dry topsoil at the time of the cold spell, as well as very limited snow cover (only 1-2 inches received for the majority of the wheat growing region in Kansas, as compared to as much as 10 inches in parts of Oklahoma and up to 20 inches in parts of Nebraska). While the three factors above increase the chances for winterkill, one promising factor at the time was that soil temperatures at the 2-inch depth never reached single digits, being usually sustained above ~12-14°F in north-central and northwest Kansas, and at higher temperatures in other parts of the state. The temperature at this depth is important as it reflects the environment where the crown of the crop is located, and minimum temperatures at single digits or lower can increase the chances of winterkill, as seen in past years in Kansas. At any rate, the potential for winterkill from the aforementioned factors would be greater in a small (late-emerged) crop, as it would have less tillers and a less developed root system, being less cold hardy. At the moment, several field visits across the state have not resulted in visible widespread winterkill, so the perspective is positive

Recent weather conditions

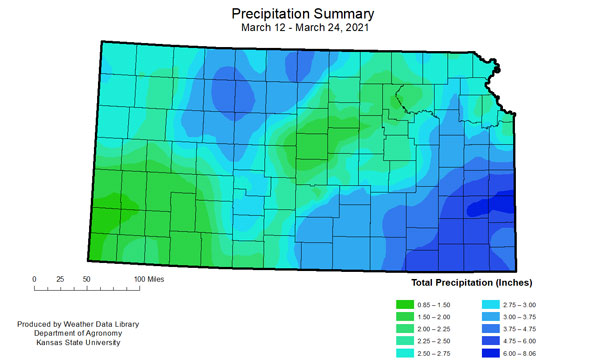

In the period between March 12-24, there was anywhere from 0.85 to 8 inches of precipitation accumulation across the state (Figure 5). This precipitation will definitely bring several benefits to the crop: (i) improve the chances of recovery from any potential winter damage; (ii) incorporate the N and S fertilizers topdressed earlier in the year; (iii) promote spring tillering, which can still contribute to yield especially in the late-emerged crop; (iv) match the period with increasing water demand in the spring as the crop elongates the stem, likely being used more efficiently by the crop.

Figure 5. Total precipitation for the period of March 12-24, 2020. Map by the Weather Data Library.

How efficiently can the wheat crop use the available water?

A survey of 654 commercial wheat fields in Kansas during 2016-2018 showed that the average water use efficiency for wheat in Kansas is about 2 bushels per acre per inch of available water (rainfall plus soil water stored at sowing). However, some fields were as efficient as ~5-8 bushels per acre per inch if the precipitation was timely and used more efficiently, coupled with appropriate management. These recent precipitation events were definitely timely, so might be used efficiently by the Kansas wheat crop.

Romulo Lollato, Extension wheat and forage specialist

lollato@ksu.edu

Mary Knapp, Weather Data Library

mknapp@ksu.edu

Tags: wheat development crop progress