Have you found yourself asking this question: “Why do the storms keep missing most of Kansas to the east/south and will it continue?” The one sure thing with weather is it always changes. Let’s look at what has happened, the current scenario, and what the forecast looks like heading into spring.

Winter Summary – November until present

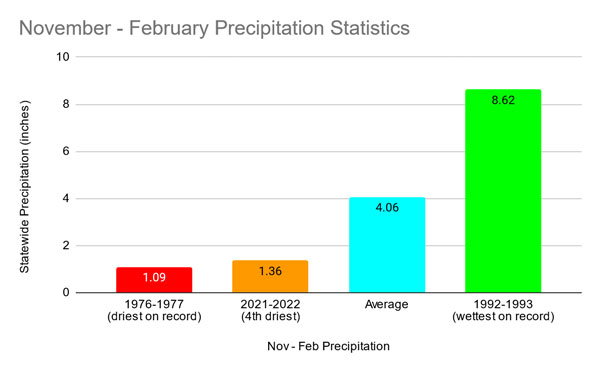

Meteorological winter ends in a week with the arrival of March. Thus far in winter, we have observed a very warm December and more a seasonable January and February. However, one thing has been consistent: it has been dry. A majority of our precipitation has fallen in January/February and mostly as snow (or some type of frozen precipitation). Despite this moisture, much of the state continues to see below-average snowfall and below-to-near record dryness. Statewide, the time period of November through February (as of 2/23/22) was the fourth driest on record. If Kansas receives no more moisture in February, there is the potential to break that record.

Figure 1. November 2021 through February 23, 2022 precipitation for Kansas is the fourth driest on record (Source: K-State Weather Data Library).

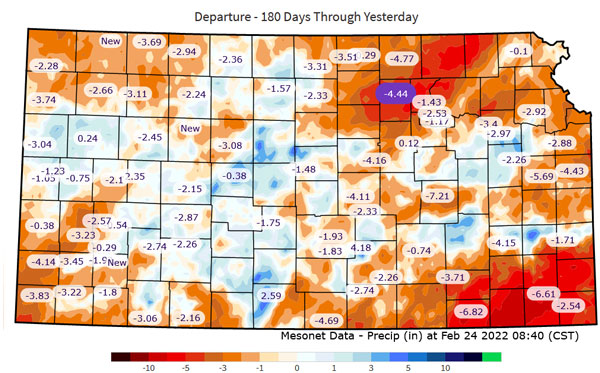

The only areas of the state that have observed any above normal precipitation (Figure 2) are the areas in west central (which observed a heavy snow event in January) and northeast Kansas (where a narrow band of thunderstorms dropped heavy rain in early November). Since that time, deficits have grown as much as – 4 inches in the east and - 1 to – 3 inches elsewhere. This is the result of a classic La Niña pattern which has held the state siege. Wetter conditions exist to the east in the Midwest, avoiding most of the state. In addition, much colder temperatures have resided to our north, with warmer conditions to the south.

Figure 2. Precipitation departures from normal on the Kansas Mesonet with National Weather Service QPE gridded data since October 26, 2021 (Source: Kansas Mesonet, https://mesonet.k-state.edu/precip/daily/).

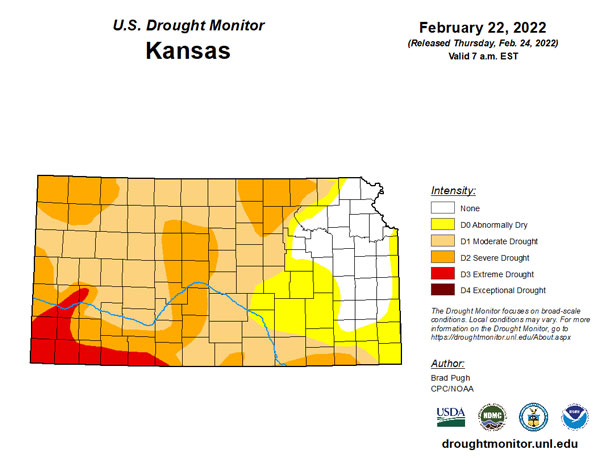

With persistent short precipitation, drought continues to expand across the state (Figure 3). Severe drought or worse conditions have expanded to 31% of the state since January 1st. Drought free areas of the state have shrunk to only 14%. Impacts from the growing drought have consisted of ideal calving conditions but also increased surface water evaporation, poor cover crop/wheat performance, depleting surface water moisture, and increased wildfire potential.

Figure 3. Drought conditions for Kansas as of February 22, 2022 (map released on February 24). Source: https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/.

Forecast for March

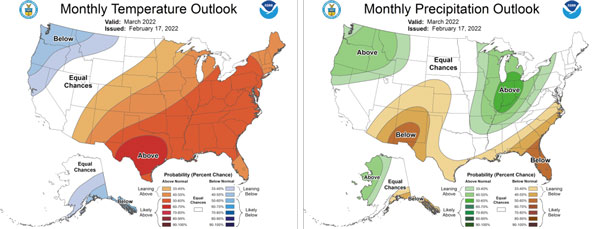

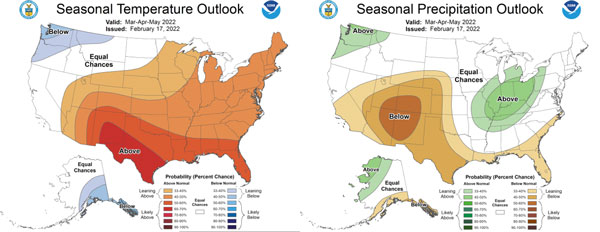

Unfortunately, no big pattern change towards above-normal moisture is expected. La Niña is forecasted to begin the slow climb (an increase in east Pacific surface water temperatures) towards neutral conditions. While that may seem optimistic, a diminishing La Niña in spring, especially a second consecutive winter with such conditions, tends to bring with it a very active pattern. We have begun to see that already in mid-February. However, the favored eastern track of moisture could potentially begin shifting westward compared to previous weeks. As a result, the Climate Prediction Center’s (CPC) outlook for March favors equal chances of above/below/average precipitation in the east (Figure 4). However, that isn’t good news for the western two-thirds of the state which has higher favor toward continued drier than normal conditions. There is much more confidence that even as the precipitation corridor shifts west, it won’t shift enough to benefit the western half of Kansas. To compile even further, an active pattern will increase the strong south/southwest wind events for west Kansas. With substantial drought further south/west, this means pushes of warm/dry air conducive for wildfire concerns and blowing dust.

Figure 4. Climate Prediction Center temperature (left) and precipitation (right) outlooks for March as of 2/17/22 (Source: CPC).

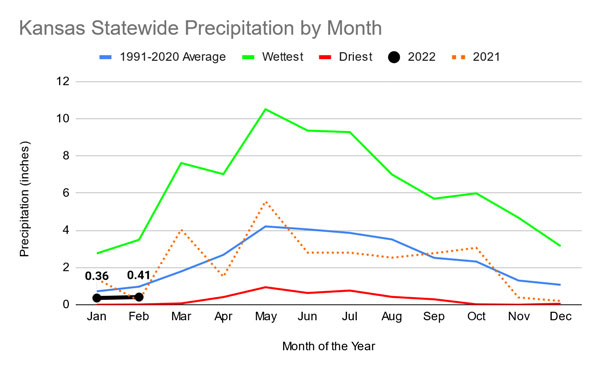

While the forecast isn’t overly optimistic, there is one positive. Despite a dry first two months of 2022, precipitation climatically trends upward with each month (Figure 5). Therefore, while below average may not be ideal, it doesn’t mean the tap will be completely cut off. In fact, with a similar ENSO pattern and February precipitation to last year, March 2021 was well above normal precipitation-wise.

Figure 5. Kansas statewide precipitation averages compared to normal (blue line), 2021 (orange line), 2022 (black line), and the wettest/driest month (green/red lines) on record. Source: Kansas Weather Data Library.

Full Spring Outlook

Long-term models show similar trends to March for the remaining spring months of April and May. As a result, the CPC placed increased favor towards below normal precipitation in western Kansas and above normal temperatures statewide (Figure 6). This would sustain an active period through spring. As we get further into spring, the average precipitation increases as does the ability to transport tropical moisture from the Gulf of Mexico northward. This would likely favor an increase in severe weather, especially for eastern Kansas. In 2021, we saw an uptick in tornadoes in May which was more than that observed in 2020. As a result, this pattern could feature a more active severe weather season. Diminishing La Nina’s often support more severe weather events. Unfortunately, continued negative outlooks for moisture will likely lead to struggles for winter wheat in central/west Kansas. Spring planting may also be impacted by decreased soil moisture and warmer than normal temperatures.

Figure 6. Climate Prediction Center average forecasts for the March-May 2022 timeframe for temperature and precipitation, updated on 2/17/22 (Source: CPC).

Christopher “Chip” Redmond - Kansas Mesonet Manager

christopherredmond@ksu.edu

Tags: weather spring outlook climate