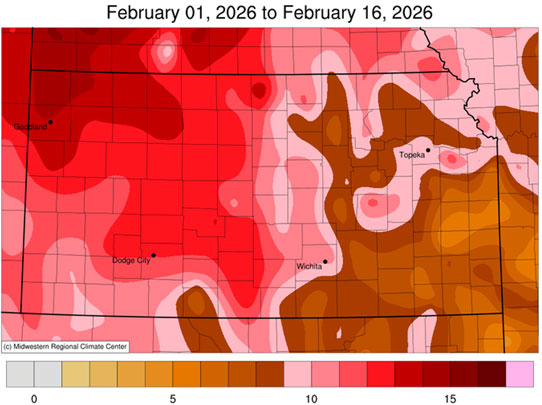

After the cold snap in late January, temperatures have been on the rise. In fact, since the start of February, average temperatures have been as much as 12-13°F above normal (Figure 1). The forecast indicates that while we will have a brief period of near-normal conditions this weekend, warmer-than-normal conditions are expected to return in March. The effects of these warmer-than-average temperatures on the wheat crop are concerning producers and crop consultants.

Figure 1. Departure from normal weekly mean temperatures for the period February 1-16 from the Midwest Regional Climate Center.

How warm have soil temperatures been?

The physiology of wheat vernalization and cold hardiness suggests that soil temperatures at the crown level, rather than air temperatures, should be the primary driver leading to increased or decreased cold hardiness during the winter. Soil temperatures will be influenced by the amount of residue on the soil surface as well as by soil moisture. Soils with a thick surface residue layer often have lower temperatures than bare soils, as the residue blocks direct sunlight and reduces evaporation, generally conserving more moisture. Moist soils require more energy than dry soils to cause any temperature change; thus, any increase or decrease in temperature occurs more slowly than in dry soils.

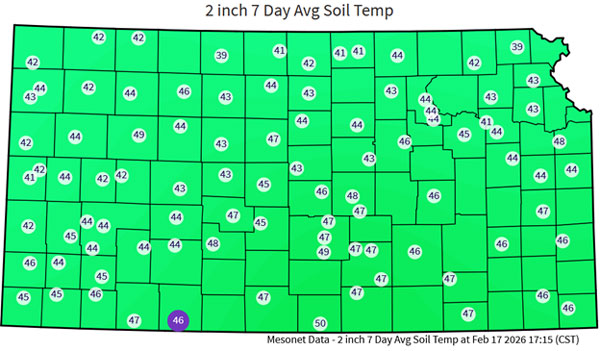

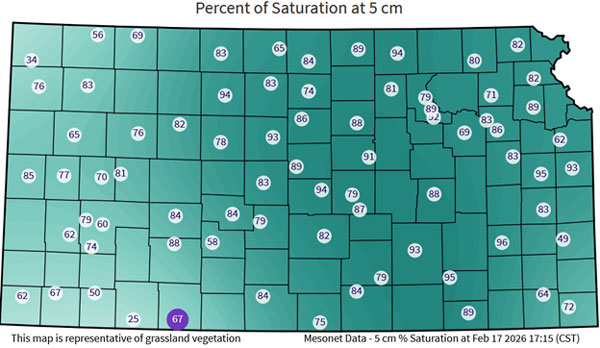

Soil temperatures at the 2-inch depth ranged from less than 39°F in the northeast portion of the state to as high as 50°F in the southern border of the state (Figure 2). The warmest soil temperatures were in the southern three tiers of counties, east from Comanche/Kiowa/Edwards counties. Soil moisture in this region (Figure 2, bottom panel) is fairly high after the recent rainfall, ranging from 70% to 90% saturated.

Figure 2. Weekly 2-inch average soil temperatures across the state of Kansas during the February 10-17 period (upper panel) and coinciding soil moisture percent saturation at the same depth (lower panel).

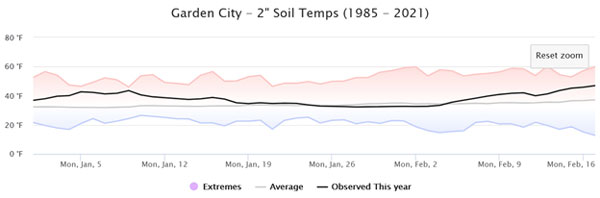

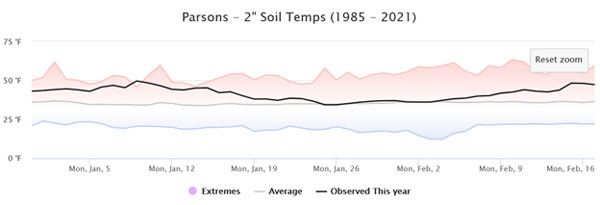

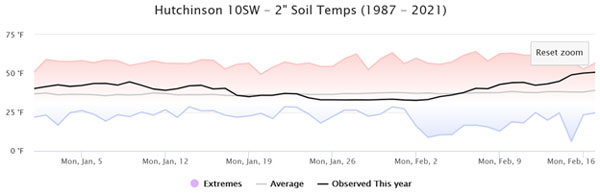

Average temperatures are very close to the 48°F threshold for winter wheat to begin losing cold hardiness (Figure 3). In particular, locations such as Garden City, Parsons, and Hutchinson are trending well above normal and exceeding the 48°F threshold.

Figure 3. Soil temperature trends compared to normal at the 2-inch depth during the 1/1/20126 to 2/8/2026 period.

Understanding the vernalization process in winter wheat

Winter hardiness or cold tolerance is a physiological process triggered by gradually cooling temperatures in the fall. During cold acclimation, there is a reduction in cell moisture content in the crown, which slows growth and the accumulation of soluble carbohydrates, both of which help protect cell membranes from freeze damage.

The process of cold acclimation within a sufficiently developed wheat seedling begins when soil temperatures at crown depth fall below about 50°F. Wheat plants will acclimate twice as fast when crown temperatures are 32°F as compared to 40°F. Photoperiod also plays a role in cold hardening, with shorter days and longer nights helping initiate it. Winter survival depends on the crown remaining alive, and the substances that produce cold acclimation are most needed within the crown.

It takes about 4 to 6 weeks of soil temperatures below 50°F at the depth of the crown for winter wheat to fully cold harden. The colder the soil at the crown depth, the more quickly the plants will develop winter hardiness.

Temperature fluctuations during the winter and their effects on wheat cold hardiness

Cold hardiness is not a static state. After the cold hardening process begins in the fall, wheat plants can rapidly unharden when soil temperatures at the crown depth rise above 50°F, but reharden as the crown temperature cools below 50°F. By the time winter begins, winter wheat will normally have reached its maximum level of cold hardiness. Wheat in Kansas typically reaches its maximum winter hardiness from mid-December to mid-January, unless high temperatures occur during that period.

Once winter wheat has reached the level of full cold hardiness, it will remain cold hardy as long as crown temperatures remain below about 32 degrees – assuming the plants had a good supply of energy going into the winter.

If soil temperatures at the crown depth rise to 50°F or more for a prolonged period, there will be a gradual loss of cold hardiness, even in the middle of winter. The warmer the crown temperature during winter, the more quickly the plants will begin to lose their maximum level of cold hardiness. Winter wheat can re-harden during the winter if it loses its full level of winter hardiness, but it will not regain its maximum level of winter hardiness.

As soil temperatures at the crown level rise to 50°F or more, usually in late winter or spring, winter wheat will gradually lose its winter hardiness entirely. Photoperiod also plays a role in this process. A sign of wheat de-hardening will be leaves changing from prostrate to upright.

Possible consequences to the wheat crop

The effect of the high soil temperatures in the late-January to early-February period on the wheat crop will depend on several factors, particularly on temperatures during the remainder of February and early March.

Where temperatures were consistently close to 50°F and fluctuated little during the recent period, as in many areas of southern Kansas, the high temperatures should cause a gradual loss of cold hardiness. The warmer the crown temperature has been during this recent period, the more quickly the plants will begin to lose their maximum level of cold hardiness.

The forecast indicates that while we will have a brief period of near-normal conditions this weekend, warmer-than-normal temperatures are expected to return in March. Winter wheat can re-harden to some extent during the winter, even if it loses its full level of winter hardiness, but it will not regain its maximum level of winter hardiness. Thus, in the regions where soil temperatures have been warmest, the crop may be less tolerant to low temperatures for the remainder of this winter, becoming more susceptible to freeze injury if temperatures decrease to single digits in the near future.

Logan Simon, Southwest Area Agronomist

lsimon@ksu.edu

Tina Sullivan, Northeast Area Agronomist

tsullivan@ksu.edu

Jeanne Falk Jones, Northwest Area Agronomist

jfalkjones@ksu.edu

Christopher “Chip” Redmond, Kansas Mesonet Manager

christopherredmond@ksu.edu