That is the question I get almost daily this time of year. We have emerged from the “deep freeze” of up to 110 consecutive hours below freezing in late January, and now temperatures have rebounded well above normal. This has been welcomed by some, especially those who are calving. However, there is still a need for cold as we enter late winter to keep vegetation dormant and reduce pest numbers.

Current Conditions

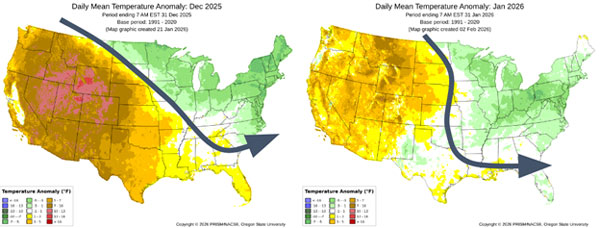

The overall winter pattern has been heavily influenced by La Niña conditions (cooler-than-normal water in the equatorial Pacific Ocean region known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation, ENSO) and its typical influence on the US. This results in a northwest-to-southeast-oriented jet stream across the central US (Figure 1), dividing the region into northeast cooler/wetter conditions and west warmer/drier conditions. This leaves Kansas in the “battleground” of these conditions, resulting in periods of both conditions as the jet stream fluctuates back and forth. There have been other impacts on the current and forecasted patterns. However, for simplicity, we will focus on the ENSO here.

Figure 1. Monthly temperature anomalies for December 2025 (left) and January 2026 (right), and the prevailing jet stream for each month annotated. Source for images is PRISM (https://prism.oregonstate.edu/comparisons/anomalies.php) with annotations by Chip Redmond, K-State Extension.

False Spring

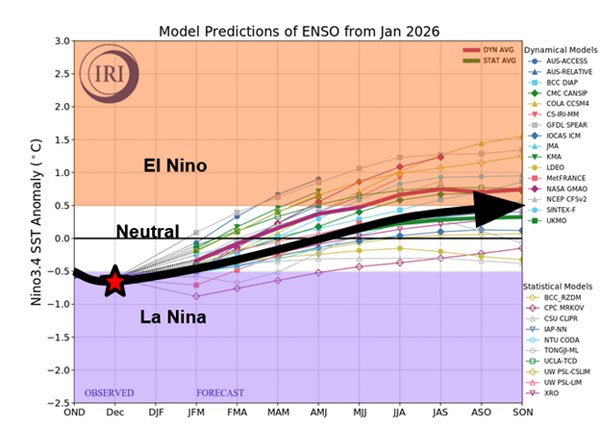

Everyone is bracing for it - like January, will the door slam shut on us with cold and snow again before we enter true spring? A transition in the weather pattern suggests the worst winter conditions are likely behind us. Sub-surface warmer water has been pushing eastward underneath those colder equatorial Pacific sea surface temperatures. This is the writing on the wall for the end of La Niña, with already moderating sea temperatures, with models projecting at least neutral to perhaps El Niño by early summer (Figure 2). Historically, when La Niña ends in the spring months, an active central US pattern typically emerges. This reduces the staying power of any cold air with frequent oscillations between warm/cold. Models seem to already be trending towards a “more active” pattern with increasing storm events as we transition towards mid-to-late February.

Figure 2. Current analysis (star) and overall projection of the El Niño Southern Oscillation for the coming months (black arrow). Data from IRI (https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/) annotated and edited by Chip Redmond, K-State Extension.

Fire First

An active pattern can be a relative term that, unfortunately, doesn’t always imply more moisture. In a waning La Niña, the pattern tracks storm systems to the east of Kansas. This shifts the Gulf moisture away from Kansas, with more wind events and overall dryness. When we look outside Kansas, drought is already slowly creeping in from almost every direction. This dryness is not favorable with the significant grass growth statewide from last year’s favorable growing conditions. Grass is the primary carrier for wildfires in the state, and with more of it, combined with increased wind and dry conditions, it seems very likely we will see an increase in wildfire activity. Additionally, we see the most acres burned in Kansas during La Niña events. Wildfire and strong wind events are expected to be the highest-impact weather events through March.

Severe Weather Second

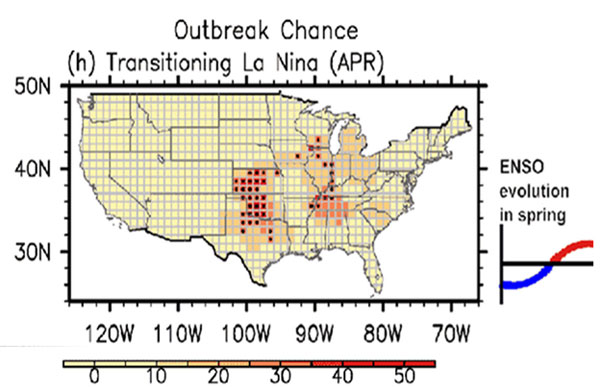

The “good news” is that the transition of La Niña is currently expected towards late March. A jet stream shift north/west is typical in April under such circumstances. Moisture is then more likely to stream into the region as we enter the middle of spring. Subsequent rainfall would likely bring a quick end to wildfire activity. However, this moisture usually comes at a cost in the spring. An increase in severe weather usually accompanies an early spring moisture influx. If we examine previous winter La Niña transitioning to El Niño summers (1951, 1965, 1972, 1997, 2023), all observed Kansas tornado outbreaks. Recent research shows a 50% increase in the probability of Kansas tornado outbreaks during April La Niña-to-El Niño transitions (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Areas that favor increased probability for tornado outbreaks during winter La Niña April transitions to El Niño. Source: https://www.gfdl.noaa.gov/research_highlight/u-s-regional-tornado-outbreaks-and-their-links-to-spring-enso-phases-and-north-atlantic-sst-variability/.

Beyond Spring

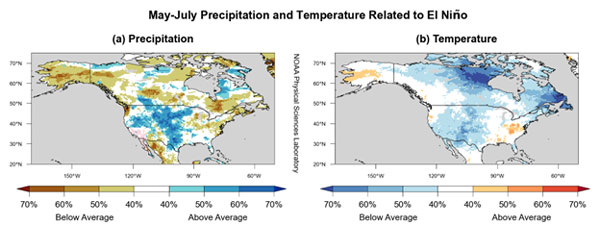

The spring seasons mentioned above still had some dry areas. A lot of what happens beyond spring is going to heavily weigh on where spring moisture focuses. Additionally, if El Niño does develop, Kansas is typically favored towards below-normal temperatures and above-normal moisture (Figure 4). These historical trends are optimistic compared to previous summer outlooks. An area to watch will be the Oklahoma/Texas drought to the south. Dryness in this region can expand northward in summer, especially if the southwest monsoon is weak. Models vary in expected monsoonal intensity. Additionally, El Niño can suppress this monsoon moisture, leading to dryness in western/southern Kansas. Local trends will be important into the summer and can easily override large-scale patterns, which create forecasting challenges. Still, I’m fairly optimistic that this summer will trend towards at least timely moisture for most.

Figure 4. El Niño trends for precipitation (left) and temperature (right) during the summer. Source: https://psl.noaa.gov/enso/fewsnet/.

Take Home Message

- Climatology says the harshest winter conditions are behind us, and warmer-than-normal temperatures are favored through the remainder of winter.

- A transition from La Niña to neutral (or even El Niño) this spring favors active fire weather conditions through March.

- This transition will likely become a wetter pattern with normal to above-normal severe weather for Kansas in April. This wetter trend should mitigate growing drought and continue timely precipitation into early summer.

- There is some potential for the Oklahoma/Texas dryness to expand northward in late summer, but that will weigh heavily on the monsoon.

Christopher “Chip” Redmond, Associate Meteorologist, Kansas Mesonet Manager

christopherredmond@ksu.edu

Tags: weather Climate winter outlook