Kansas’ growing season began on April 1. The first month of this season was a dry one across most of the state (Table 1). The April statewide average precipitation of 1.32” was just 49% of normal. This ranked as the 17th driest April on record out of 129 years, dating back to 1895. All but one of Kansas’ nine climate divisions averaged below normal. Northwest Kansas was driest; their 0.42” was just 21% of normal and ranked as the 7th driest on record. Southeast Kansas’ total was higher, 1.26”, but was only 30% of normal, and also ranked as 7th driest. The only division to finish April above normal was southwest Kansas, where an average of 1.92” of precipitation fell; this total ranked as the 46th wettest April on record in that division. Southwest Kansas would have finished the month below normal had it not been for a late-month precipitation event that brought 2 to 3” over a large part of that division between the 25th and 28th. The heavy rain led to a 1-category improvement in the US Drought Monitor in the May 2nd update, placing parts of southwest Kansas back in D3 after a 6 to 9-month period of being in D4, the most severe drought category. Unfortunately, parts of northwest, central, and south central Kansas had worsening drought conditions in April and were moved from D3 down to D4.

Table 1. Total precipitation (inches) by Kansas climate division for the month of April 2023 and estimated total precipitation for May 1-22, 2023. Numbers in parentheses are the departures from the 30-year normal)

|

Division |

Precipitation |

||

|

April (Departure) |

May 1-22 (Departure) |

Total (Departure) |

|

|

Northwest |

0.42” (-1.56”) |

3.64” (+1.33”) |

4.06” (-0.23”) |

|

North Central |

0.91” (-1.55”) |

2.91” (-0.52”) |

3.82” (-2.07”) |

|

Northeast |

2.51” (-0.97”) |

3.18” (-0.16”) |

5.69” (-1.13”) |

|

West Central |

0.85” (-0.91”) |

2.63” (+0.54”) |

3.48” (-0.37”) |

|

Central |

0.99” (-1.48”) |

2.60” (-0.19”) |

3.59” (-1.67”) |

|

East Central |

1.60” (-2.15”) |

2.83” (-0.66”) |

4.43” (-2.81”) |

|

Southwest |

1.92” (+0.25”) |

2.59” (+0.61”) |

4.51” (+0.97”) |

|

South Central |

1.38” (-1.24”) |

2.34” (-0.33”) |

3.72” (-1.57”) |

|

Southeast |

1.26” (-2.88”) |

3.33” (-0.24”) |

4.59” (-3.12”) |

|

STATE |

1.32” (-1.36”) |

2.79” (+0.03”) |

4.11” (-1.33”) |

Starting to improve

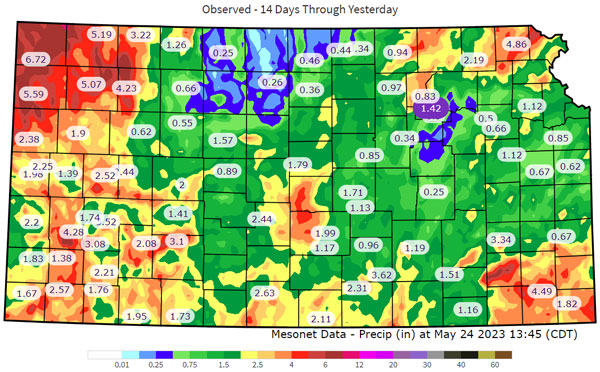

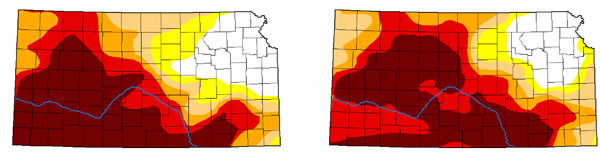

May is typically one of the wetter months of the year, and while all divisions have had more precipitation so far in May than they did in April, only the three western Kansas climate divisions are averaging above normal for the month as of May 22. The remainder of the state is below normal, but departures from normal in these areas are two-thirds of an inch or less. Northwest Kansas, often one of the driest divisions of the state, is currently averaging the highest precipitation in the state. This is due mainly to a heavy rain event that brought 3 to 5” of rain to much of the area between May 10-12. Statewide, precipitation over the last 14 days (Figure 1) has been heaviest in the northwest and southeast corners of the state. Parts of north central Kansas have missed out on the higher rainfall totals, and recent US Drought Monitor updates have continued to show worsening conditions in this division (Figure 2).

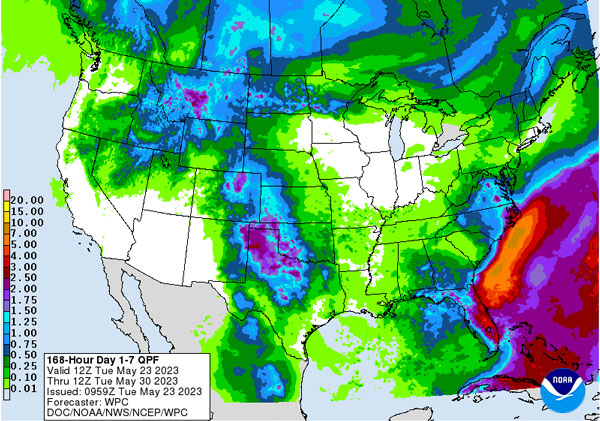

The 7-day precipitation forecast for the last week in May (Figure 3) suggests western Kansas should finish the month above normal, while eastern and central Kansas are likely to finish below normal. At this time of year, any extended period without rain can rapidly increase precipitation deficits. For the last 7 days of May, precipitation averages around 0.80” in the western third of the state, 1.10” in the central third, and 1.25” in the eastern third. For the eastern two-thirds of Kansas, where deficits for the growing season currently range from 1.1” to 3.1”, another week with below normal precipitation, as is currently forecast, is not welcome news.

Figure 1. 14-day precipitation totals as of 11 AM CDT on May 23, 2023 across the Kansas Mesonet network.

Figure 2. US Drought Monitor map for Kansas on March 28, 2023 (left) and May 16, 2023 (right).

Figure 3. The Weather Prediction Center’s 7-day total precipitation forecast for May 23-30, 2023.

Looking to the future

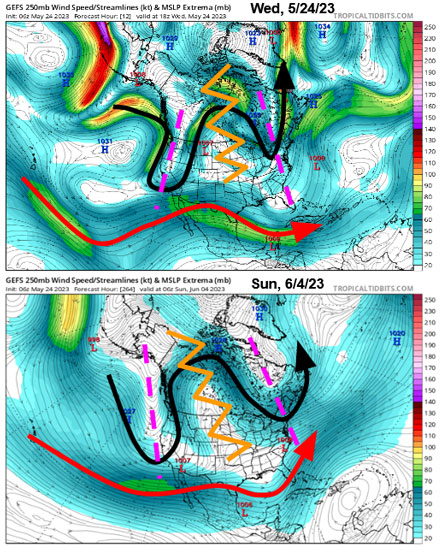

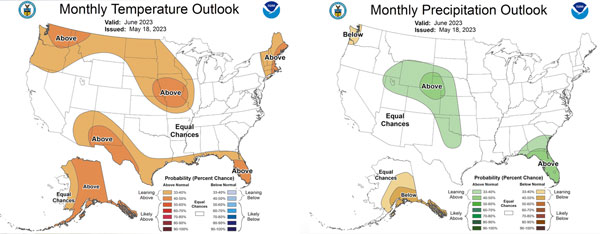

The current configuration of the upper atmosphere is stuck in what we meteorologists call a “blocking pattern.” While this has resulted in moisture in the west, it isn’t spreading the moisture statewide. This “omega block” as we call the current configuration (Figure 4), is notoriously difficult to forecast/model. In fact, the current depiction of the pattern (Wed, 5/24/23; Figure 4 top) is extremely similar to the pattern modeled over a week out (Sun, 6/4/23; Figure 4 bottom). Therefore, the pattern is expected to remain incredibly consistent into June. Even the current June Climate Prediction Center outlooks favor similar conditions to the last week through the month (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Upper-level wind patterns over North America from the GEFS forecast model on Wednesday (5/24/23 top) and on Sunday (6/4/23 bottom). The jet stream remains in split flow with the northern jet (black) in a persistent omega block (a ridge, orange jagged line bookended by two troughs of low pressure in the dashed purple lines) and the southern Jetstream (red) in a weak flow but ample enough to transport Gulf moisture north into the High Plains. Image source: tropicaltidbits.com with annotation by Chip Redmond, Kansas Mesonet Manager.

Figure 5. June temperature (left) and precipitation (right) outlooks from the Climate Prediction Center.

There are currently two factors that may help degrade the current pattern towards something more progressive. While we need continued moisture across the western part of the state, much of central and eastern Kansas is observing a growing precipitation demand. The first hope is the degradation of the strongly negative Pacific Decadal Oscillation. It strengthened last month and the cold Pacific water off the West Coast definitely aided the development of this pattern. However, these waters have begun to warm up in recent weeks. Should this diminish the –PDO, it would help suppress high pressure across western Canada and the northwest US and allow for a more active overall pattern. It would just take time, potentially not until mid-to-late June, which could be too late for some crops and water sources in the central/east.

A second area of hope to expand precipitation is the current typhoon Mawar impacting Guam. Some medium-range forecast models show this storm slowly moving to the west/northwest and eventually becoming wrapped into the northern jet stream. This may be just enough to kick the pattern out and finally break down the persistent ridge. Although the impacts are still greatly in question, its presence presents the potential opportunity for a potentially active western Pacific typhoon season.

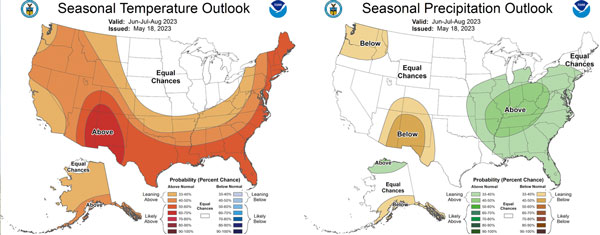

Notice, we haven’t mentioned the notorious El Niño Southern Oscillation. During the winter, ENSO is typically the least impactful for Kansas. Therefore, the current summer outlook for average overall of June, July and August, mostly favors equal chances of at/below/near normal conditions for a majority of the state (Figure 6). Warmer than normal temperatures are slightly favored with summer post-La Niña favoring southwest US dryness/warmth. This seems a likely outcome with conditions potentially drying out this summer for the High Plains. However, some increased favorability resides along the Missouri border should El Niño dominate earlier than thought. This overall switch in the pattern may be favorable for agriculture in the state.

Figure 6. June, July, and August average temperature (left) and precipitation (right) outlooks from the Climate Prediction Center.

Considering further into the future

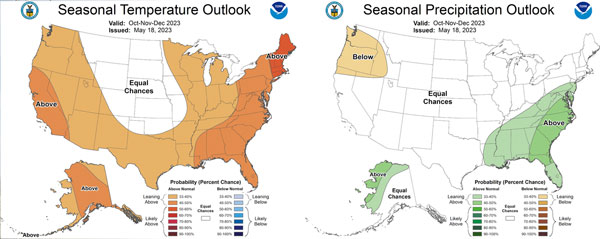

Now we are currently in an El Niño watch with a 70% probability of El Niño emerging in the eastern Pacific this summer. This is a pretty high potential, however, should the current neutral conditions (remember, we already got rid of La Niña, that is a start) evolve into warmer El Niño waters, impacts would be assumed to begin in the late fall and early winter. There is quite a bit of favorability in the models of increasing Kansas moisture especially come October/November timeframe. This wouldn’t help the current crop but is something to consider for next year’s winter wheat. El Niño strengthens the southern jet stream and results in cool/wet conditions to our south and warmer conditions to our north. That would once again, like La Niña, put us in the battleground of uncertainty. Current CPC outlooks hold to the uncertainty with equal chances statewide through the end of the year (Figure 7).

Figure 7. October, November, and December average temperature (left) and precipitation (right) outlooks from the Climate Prediction Center.

Matthew Sittel, Assistant State Climatologist

msittel@ksu.edu

Christopher “Chip” Redmond, Kansas Mesonet Manager

christopherredmond@ksu.edu