Planting date studies have been conducted for corn over many years. Often the focus has been to determine optimum planting date for maximizing yield. In some areas, planting early-maturing corn hybrids as early as possible has been a successful strategy for avoiding hot, dry conditions at the critical pollination and early grain fill stages.

Planting later can be an alternative strategy that attempts to avoid the most intense heat by moving the critical growth stages for corn centered around pollination to later in the growing season. This strategy has been adopted by some growers in areas that often encounter heat and moisture stress during the growing season. However, crop insurance cutoff dates for planting are earlier than some farmers may want to plant some of their corn acres.

Studies in Ottawa and Topeka, 2018-2020

A series of studies was conducted at the East Central Experiment field (dryland) near Ottawa and the Kansas River Valley Field (irrigated) near Topeka in 2018, 2019, and 2020. The purpose of these studies was to add to earlier studies in Kansas to assess the yield potential for corn planted after the insurance planting cutoff date and to compare corn yields from a wide range of planting dates.

As expected, the results of the 2018-2020 tests varied depending on environmental conditions, especially at the dryland location near Ottawa.

Dryland: The preliminary results from these three years of experiments provide an example of how later planting dates can be a viable option to avoid stressing the corn at critical stages when moisture is limiting, or when planting is delayed because of excess rainfall. These data also show the variable response to planting date in dryland production of corn in Kansas, which is often related to the conditions at pollination (Figures 1 and 2).

Irrigated: The results from three years of irrigated experiments at Topeka illustrate that if moisture is not limiting, but planting is delayed, corn can still produce a substantial yield, though reduced from the potential of the optimum (Figures 1 and 3).

Complete details of these studies can be found in K-State’s Kansas Field Research 2021 report: https://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8071&context=kaesrr

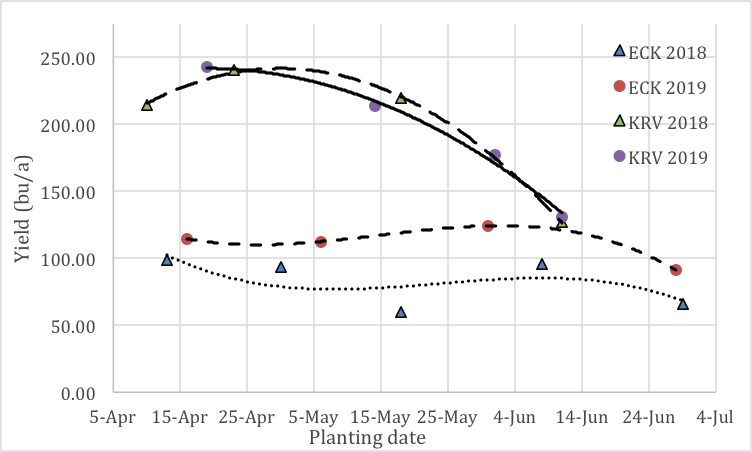

Figure 1. 2018 and 2019 yield response of corn to planting date at the East Central Kansas Experiment Field (ECK), Ottawa, and the Kansas River Valley Experiment Field-Topeka (KRV). The yield results from Ottawa were greatly influenced by hot and dry periods in July when corn planted in early to mid-May was trying to pollinate. As a result, the corn planted at the end of May or first week of June yielded as well or better than the earlier planting dates because rain events occurred when the corn was pollinating. On the other hand, corn planted in the last week of June had good pollination weather but yielded only 60–70% of the highest yields each year, reflecting the shortened growing season from planting that late. At the irrigated location near Topeka, the highest yield was when corn was planted in the last half of April in 2018 and 2019. A 111-day relative maturity hybrid was used at both locations in both 2018 and 2019.

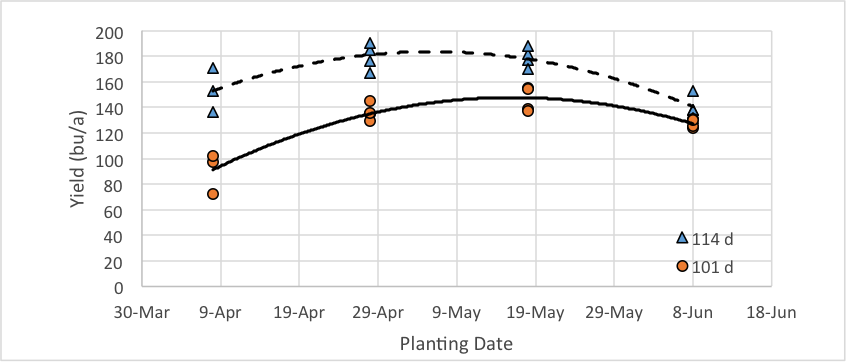

Figure 2. 2020 yield response of full- and short-season corn to planting date at the East Central Kansas Experiment Field, Ottawa. The corn yield response to planting date in Ottawa in 2020 was very different than the previous two years, with the highest yield 40 to 80 bu/acre higher than the two previous years. The above-average rainfall in July was favorable for pollination, resulting in the highest yields from corn planted at the end of April through mid-May for both the short- and full-season hybrids. Corn planted in the first week of June yielded just more than 70% of the highest yields. The full-season hybrid yielded more than the short-season at every planting date, indicating that switching to a shorter-season hybrid due to delayed planting may not increase yield.

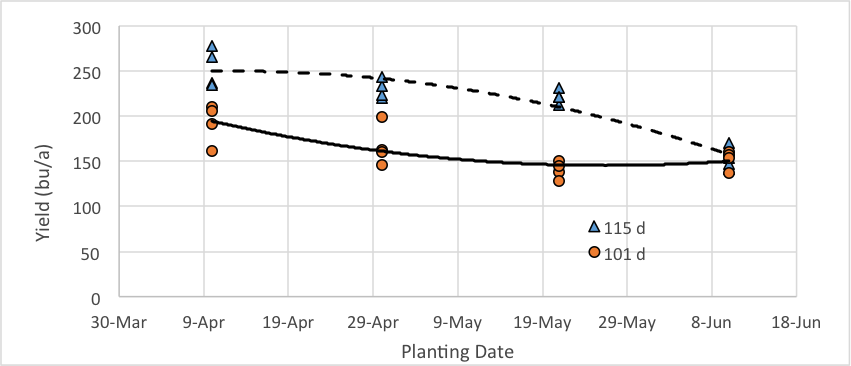

Figure 3. 2020 yield response of short- and full-season corn under irrigation to planting date at the Kansas River Valley Experiment Field, Topeka. For all years at Topeka, the yield-limiting factor of moisture stress was greatly reduced by repeated irrigations, resulting in a more traditional yield response to planting date. In 2020, the highest yield was with the April 10 planting date for both the short- and full-season hybrids. The yield of the fourth planting date of June 11 was between 50 to 60% of the high yield each year for both hybrid maturities. Similar to the results from Ottawa, switching from a full- to a shorter-season hybrid due to delayed planting did not increase yield.

Studies in Belleville, Manhattan, and Hutchinson, 2013-2014

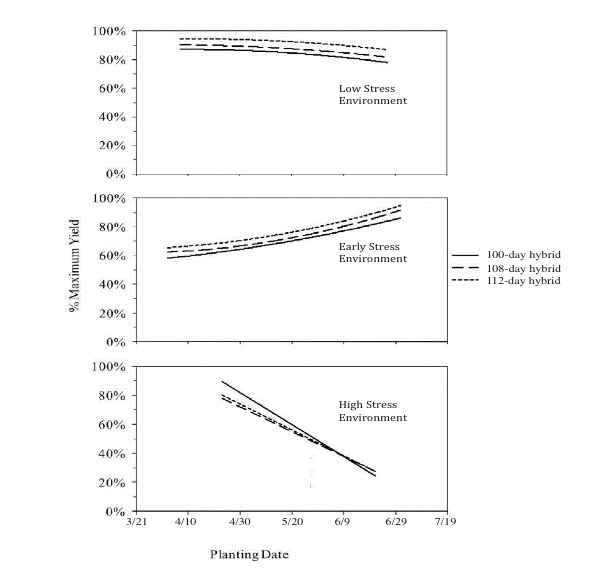

An earlier series of tests in Kansas also found that the yield of late-planted corn under dryland conditions varied considerably, and that the determining factor was often whether and when the corn was stressed during the growing season (Figure 4).

Three hybrid maturities were tested: 100-, 108-, and 112-day. Over the two years and three locations (Belleville, Manhattan, and Hutchinson) of these studies, there were three distinct environments (as related to the environmental stress):

- Low Stress – where rainfall was favorable during the entire growing season

- Early Stress – where cool temperatures and wet conditions limited early corn growth

- High Stress -- where conditions (rainfall and temperatures) were favorable early in the season, but the mid-summer was hot and dry

In the Low Stress environments, yields were reduced by less than 20% when planting was as late as mid-June. Yields were not statistically different for any planting date before May 20 (starting from early April). Maximum yield in these non-irrigated environments was 176 bu/acre. The yield responses were similar for hybrids of all maturities.

In the Early Stress environments, yields actually increased as planting was delayed until late June. This response was similar for all hybrid maturities. These environments had favorable temperatures and rainfall throughout July and early August. Maximum yield in these environments was 145 bu/acre.

In the High Stress environments (hot, dry mid-summer conditions), yields dropped by about 1% per day of planting delay, depending on hybrid maturity. The shorter-season hybrids had the best yields if they were planted before late May (maximum yield = 150 bu/acre), but all hybrids had yield reductions of more than 50% when planting was delayed until early to mid-June.

Figure 4. The top chart (Low Stress) shows how little corn yields changed as planting dates got later when growing conditions were good through the remainder of the season. The middle chart (Early Stress) shows that corn yields actually increased with later planting dates when conditions were too cool and wet early, but then became more favorable. The lower chart (High Stress) shows how dramatically corn yields decreased when conditions were favorable early in the season, but the mid-summer was hot and dry.

Another factor to consider when planting corn late is whether the crop will be mature at the time of the first fall freeze. As you move south and east from Manhattan, the risk of early termination from a fall freeze will decrease, but the risk will increase as you move north and west from Manhattan.

Summary

Yields of dryland corn are often related to the conditions at pollination. Yields of late-planted dryland corn can range from 50 to 70% to more than 100% of the highest yield of corn at earlier planting dates, depending on environmental conditions. Late-planted dryland corn does best when conditions are unfavorable (too cool and wet) early, but then become more favorable in mid-summer. On the other hand, yields of late-planted corn typically decrease dramatically when conditions are favorable early in the season, but become hot and dry in mid-summer.

Planting date is not necessarily a strong predictor of corn yield, more when our target yield environment is not for high yield levels (>200 bu/a).

When making decisions on delayed planting of corn, crop insurance considerations are often an important factor, as well as agronomic considerations.

Eric Adee, Agronomist-in-Charge, East Central and Kansas River Valley Experiment Fields

eadee@ksu.edu

Ignacio Ciampitti, Farming Systems Specialist

ciampitti@ksu.edu

Tags: corn late planting