Wheat that has been stressed by drought and extreme heat can have seed quality concerns (Figure 1). Drought conditions were prolonged in many areas of Kansas through most of the winter and spring in 2022, causing stress to plants through early grain filling stages. In addition, extreme heat occurred during the four-day period of May 9-12, which coincided with boot, flowering, pollination, and early grain fill stages depending on the area within Kansas.

Figure 1. Wheat being unloaded after harvesting. Photo by Kansas Wheat.

Drought and heat stresses on wheat, alone or in combination, can cause physiological damage that results in light test weights or small seed size. The extent of the damage depends on the severity of the stress and the stage of reproductive development.

When temperatures are very warm for more than three consecutive days during grain fill and soils are very dry, plants will senesce early and speed through this critical stage. High temperatures during the grain filling stage will slow or stop formation of starch in the kernel, consequently increasing the percentage of protein in the grain. Heat- and/or drought-stressed kernels are usually small and shriveled, resulting in lower kernel weight, lower test weight, and lower yield. The kernels simply will not fill properly.

Will the wheat grown under stressful conditions be suitable to use for seed this fall?

There’s no simple answer to this question. First of all, before considering whether to use your own wheat for seed this fall, make sure it’s allowable. While most wheat varieties are protected by Plant Variety Protection which allows for keeping seed to plant on your own acreage, additional licensing and/or marketing restrictions may apply to some varieties referred to as Certified Seed Only (CSO), which removes this allowance. Consult your seed dealer for varieties that are not allowed to be planted back.

If plant-back is an option, there are several considerations regarding the use of this year’s crop for seed. Where wheat was stressed during critical growth stages and the kernels are small or shriveled, producers should first have the wheat tested for germination, and then cleaned to a test weight of at least 55-56 pounds per bushel if possible. Another germination test after seed cleaning would be warranted to ensure proper germination percentage was achieved.

Wheat with a lighter test weight may emerge just fine -- just look at all the volunteer wheat that emerges from small or shriveled seed that is blown out the back of the combine. But below a test weight of 55-56 lbs/bushel, the plants that emerge are more likely to have problems overcoming any adverse conditions in the fall and surviving the winter. Producers planting light-test-weight seed will also have to be extra cautious not to plant the seed too deeply, since seed vigor will likely be below average. Seedlings from light-test-weight seed will also likely be less competitive than normal against weeds. Knowing this a producer should plan accordingly for weed control.

Seed that is unusually small for a given variety should be tested for germination. Producers should consider having both a standard and an accelerated aging (AA) germination test done on small shriveled wheat before using it as seed. Seed that is unusually small won’t necessarily have poor vigor or result in lower forage or grain yields in the subsequent crop, but it should be tested first and conditioned to the largest seed size possible.

Before using this year’s wheat for seed, the wheat should be cleaned with a 6/64 screen, if possible. If that cleans out far too much of the wheat, then a 5.5/64, or even a 5/64, screen will do. But no less than that. Cleaning wheat with less than a 5/64 screen will do little or no good.

How much can test weight and kernel size of the seed affect yields?

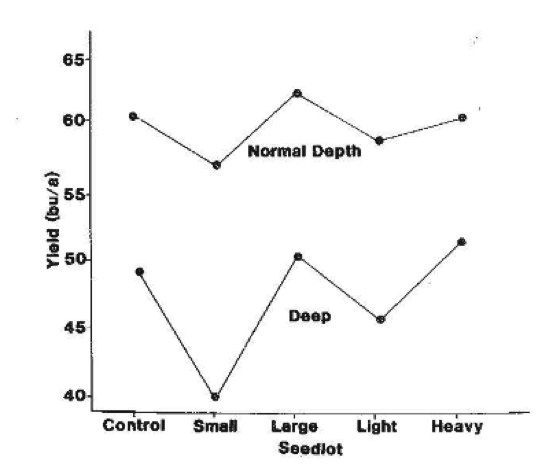

From 1980-1983 a study was conducted at the Colby Experiment Station (as it was called then) by K-State agronomist Larry Robertson. He tested the effect of seed size and test weight on yield using foundation seed of three varieties, two seeding depths, and two locations. The results showed that seed size and test weight both had an effect on yield of the subsequent crop. Yield differences of 10- 15% were measured, with the lowest yields resulting from deep seeding depths (Figure 2, Table 1). Small and/or light seed always yielded less than the control, heavy or large seed, but more so at deeper seeding depths.

Figure 2. Influence of seedlots and planting depth on yield of winter wheat. Source: “Effect of Seed Size and Density on Winter Wheat Performance”, Keeping Up With Research, K-State Research and Extension SRL74

|

Table 1. Effect of seed size and test weight on wheat yield (average of four years, two locations – Colby and Hays, and two seeding depths (normal and deep) |

|

|

Seed lot |

Yield (bu/acre) |

|

Control (entire seed lot) |

53.6 |

|

Small seed fraction (average: 21,200 seeds/lb) |

48.1 |

|

Large seed fraction (average: 9,150 seeds/lb) |

54.4 |

|

Light test weight fraction (avg test weight: 57.8 lbs/bu) |

50.2 |

|

Heavy test weight fraction (avg test weight: 62.2 lbs/bu) |

54.0 |

In addition, in 1990 a study was conducted by Jim Shroyer, Stu Duncan, and Dale Fjell, former K-State Extension specialists, on seed of Arkan wheat from 25 demonstration plots around the state. Yields averaged 2.4 bushels per acre higher with the high-test-weight seed (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Effect of test weight on yields of Arkan variety |

|

|

Test weight |

Yield (bu/acre) |

|

Light (54 lbs/bu) |

41.5 |

|

Heavy (61 lbs/bu) |

43.9 |

The effect of seed test weight on emergence, vigor, and yield potential will vary from year to year. When there is stress on the seedlings or young plants in the fall from freeze or drought or some other factor, the effect of higher test weight seed is often greatest.

Research on how seed size affects yields is a little more variable. Some research on wheat, such as the K-State study in Table 1 above, has found that yields are reduced when using small-sized seed. Bockus and Shroyer also found that sowing large seed produced plants with greater ground cover and increased forage production for producers who graze livestock. This was true especially if the large seed and small seed were sown at the same seed count per acre. There were smaller differences in forage production when the large and small seeds were sown using the same volume of seeds per acre.

More recently, K-State Extension wheat specialist Romulo Lollato and his group conducted tests on 27 environments across three years using the variety SY Monument. Results suggested a consistent yield increase of about 2 bu/acre when the seed was passed through an air screen as compared to no cleaning at all; and another 2 bu/acre when the air-screened seed went through the gravity table (see individual year reports for 2018-19 here and for 2019-20 here). This experiment also suggested a consistent yield advantage of about 1.5 bu/acre by using a fungicide and insecticide seed treatment.

Results from other studies around the country on the effect of seed size on wheat yields have varied, with some showing seed size has no effect on yield and some showing reduced yields with small seed.

Light test weight causes

Possible causes of light test weights include drought stress, heat stress, wheat streak mosaic damage, and rainy weather at harvest. Light test weights caused by rainy weather at harvest will normally not cause seed quality problems. The other causes are more likely to create some issues.

Drought stress is probably the main cause overall of light test weights. Wheat under drought stress reacts in several ways. The plants will normally allocate most of the available nutrients and water to the first kernel or two in the mesh. These kernels may be small, but often have high protein and adequate test weight. The remaining kernels will be denied the necessary nutrients and water, however. If these flowers or kernels were not aborted, then they will be shriveled and have low test weight.

Heat stress during grain fill can cause the plants to shut down deposition of starch in the grain, which can result in low test weights in most kernels on the head. It may even result in premature death of the plant, before the grain has filled. Heat stress would have to occur for several days in a row during early- to mid-grain fill to shut down the plants and reduce test weights significantly. If the period of extreme heat lasts for only 1-3 days, it’s unlikely to permanently reduce test weight, although it can reduce kernel length if it happens during grain elongation. Premature death due to heat stress is one of the most common reasons for light test weights in late-maturing varieties in Kansas.

Small seed size causes

The effect of small seed size on wheat germination, seedling vigor, and yield potential varies considerably, depending in part of the reason for the small size.

Some varieties naturally have a smaller seed size tendency than others. The range in seed sizes of modern hard red winter wheat varieties currently grown in Kansas can go from as low as 8,000 seeds per pound on the large side, to as high as 22,000 seeds per pound on the small side. Most varieties are in the range of 11,000 to 18,000 seeds per pound. Smaller-seeded varieties can have very high yield potential, so small seed size has no effect on performance in that situation.

Also, there is always a small fraction of small seed from screen-outs during the cleaning and conditioning process.

However, if most or all wheat kernels are smaller than normal because of drought stress, heat stress, or freeze damage, then the small seed may have physiological damage. In that case, the small size wheat would likely have reduced seedling vigor and yield potential, and less ability to compete with weed pressure.

Summary

Where wheat was stressed by a combination of drought and heat stress during its reproductive and grain filling stages, the kernels may have suffered physiological damage. As a result, it could have light test weights and/or small seed size. Improved grain filling conditions during the last full week of May could help maintain kernel weight and size. While this may have happened in parts of central, north central, and northwest Kansas, the crop in south central and in southwest had likely limited benefits from the recent rains and cooler temperatures.

The best option in general would be to plant certified seed, which has been cleaned and tested for germination to meet quality standards. That would remove any uncertainties about seed quality. It may be tempting to save the expense of purchasing certified seed, but once the lost yield potential is factored in, the most profitable option may be to plant certified seed. If ordering certified seed, ensure that you are “on the list” fairly early as seed supply is uncertain this year due to crop abandonment and low yields.

If the some of the stressed wheat is saved for seed, in cases where this is allowable, producers should consider having it tested by a professional seed lab for germination (both standard and AA), conditioned to get the highest test weight and largest seed size possible, and possibly treated with a fungicide. That seed should also be planted with special care to make sure it’s not too deep and has good seed-soil contact. If small seed from stressed wheat is used, it would be best to increase the seed count per acre even if germination tests are good.

Producers should try their best to plant the best quality seed possible this fall to get good emergence, early season vigor, and yield potential. It makes no sense to plant poor quality seed that will just create more problems next season. Certified seed is the best option.

Romulo Lollato, Extension Wheat and Forages Specialist

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist, Southwest Research and Extension Center

Eric Fabrizius, Associate Director, Kansas Crop Improvement Association

Guorong Zhang, Wheat Breeder, Agricultural Research Center-Hays

Lucas Haag, Northwest Area Extension Agronomist

Jeanne Falk Jones, Multi-County Extension Agronomist