The time following wheat harvest presents an opportunity to incorporate cover crops. Parts of Kansas have had enough moisture to grow a cover crop with substantial biomass production, which could also be a source of forage for livestock.

The following is a summary of “Cover Crops Grown Post-Wheat for Forage Under Dryland Conditions in the High Plains”, a fact sheet produced in collaboration with extension specialists and research scientists at Kansas State University and Colorado State University. The entire fact sheet can be viewed and downloaded at https://bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3523.pdf.

Selection of Species

Determining what to plant can be difficult with all the varied species available for use as cover crops. For Kansas producers, local Land Grant Universities, including Kansas State University, and the Midwest Cover Crops Council, have developed a decision tool to help select species based on specified goals. When cover crops are grazed, one needs to choose species that are palatable and safe as forage for livestock and will benefit soil health . Fortunately, many species currently recommended for use as cover crops are also good for forage production. Factors such as nutritive content and potential toxicities must be considered.

While some potential risks (i.e., nitrates, prussic acid, alkaloids) exist, most can be managed. Members of the sorghum family (sorghum-sudan, sudangrass, grain sorghum, and forage sorghum) and millets are common nitrate accumulators. Environmental stress and excess nitrogen can increase nitrate levels in these plants. Producers should use caution when grazing forages with high nitrate potential and test before grazing. Although a hard freeze does not change nitrate content, prussic acid toxicity can occur when grazing sorghums, particularly young plants, and in the fall following a frost/freeze. For more information, see KSRE publications on nitrate and prussic acid toxicities or consult Grazing Management: Toxic Plants (MF3244).

Goals for the timing and length of grazing are considerations in species selection. For early to late summer planting, crops can be grazed late summer through early fall. Warm-season species such as millets, sorghum-sudangrass, sudangrass, forage sorghum, sunflowers, cowpeas, lablab, or sunn hemp should be considered potential species to grow. Sudangrass and sorghum-sudangrass have good regrowth potential and could be grazed a couple of times from summer through fall if ample moisture is available for regrowth and planted early enough in the year. Alternatively, biomass can be allowed to accumulate and grazed 7–10 days after a hard freeze to reduce prussic acid risk. Though cattle may trample significant biomass during late-season grazing, this strategy may support soil health goals by increasing soil cover.

Complex mixtures of 6 or more species, often called “cocktails,” are commonly promoted. Research studies at Kansas State University and other universities have not found a benefit to cocktails compared to single species or simple mixtures of 2 to 4 species. Competitive warm-season grasses typically produce the most biomass, enhancing both forage yield and weed control. While mixtures may provide other benefits, such as nitrogen fixation from legumes or pest suppression from brassicas, measurable increases in soil nitrogen from legumes are rare in High Plains studies. From a grazing perspective, mixtures can produce forage with a range of palatability that can provide benefits and limitations. However, herbicide options are greatly limited when growing a mixture of grass and broadleaf species as a cover crop.

Variability in Forage Production

Under dryland conditions, forage productivity will vary from year to year, which makes this one of the biggest challenges facing producers who graze cover crops in the High Plains Region because stocking rates will need to be adjusted annually.

Producers have several options to manage this variability in forage production. A flexible herd size where animals can be added or subtracted based on a given year's productivity is the ideal situation. However, it is difficult for most to adjust herd size, so the number of days a field can be grazed will have to be shortened or lengthened to achieve residue goals. In reality, expect to graze cover crops planted post-wheat for about 30 days in most years. This resource should be considered supplemental forage during the late summer and early winter to help relieve dependence on other forage resources such as native rangeland and baled hay.

If excess forage is produced, putting some up as hay or silage to preserve forage for dry years may be a good option. However, removing hay and silage could reduce the amount of residue left in the field, negating soil health goals compared to grazing. Resting native pasture going into the fall is the most critical time for native species to store carbohydrates. This is always a good time to rest native pasture, especially following the drought years. By using summer annuals in the fall, native pasture can be stockpiled and grazed later in the winter after the grass is dormant, reducing winter feed expense.

As a final note, in years with minimal precipitation and forage productivity (i.e. ~1,000 lb/ac or less), the best choice might be not to graze at all if your primary goal is soil protection. Ideally, you want to maintain a minimum of 30% ground cover or approximately 1,000 lb/ac.

Figure 1. Top image was taken in mid-August during a field day at a study field north of Bird City, Kansas. Bottom image was taken at the end of the grazing period that started in January. The heifers are standing at the end of the grazing area. The previously grazed strip is to the right of the fence line.

Grazing Management

When managing grazing of cover crops, numerous options can be considered. The ultimate strategy chosen will be influenced by your overarching goal(s) for the cover crop. Cover crops are generally grown for more reasons than just achieving high levels of harvest efficiency (i.e., percent utilization of available forage), as you would if this were a dedicated forage crop. You want to leave enough residue to maintain most of the benefits associated with planting cover crops.

Grazing management options include:

- Continuous grazing: Calculate a stocking rate based on the estimated yield and put the whole herd in one large field. Advantages are that no fences are moved and only one water source is needed (i.e., labor and inputs are minimal). However, if the field is large, livestock will tend to overgraze the forage closest to the water source while underutilizing the forage farthest from the water, unless you can move the watering location. Harvest efficiency will generally be around 30%.

- Rotational grazing: A large field is divided into two or more smaller units, or paddocks, and the animals are rotated from one paddock to the next. This option has some advantages and disadvantages. The more paddocks the field is divided into, the higher the stocking density (i.e., the number of animals per acre). Key concerns include maintaining residue levels and minimizing soil compaction. Frequent fence movement and managing water access are two of the main challenges that discourage the use of rotational grazing.

- Strip grazing: This differs from rotational grazing in that there is no back fence, and animals can graze both fresh, residual, and regrowth forage. This is convenient for watering animals as the fence can be set up so they have continuous access to a single water point. One drawback is increased compaction near the water source. Regrowth is limited since animals revisit previously grazed areas.

The next decision to make is when to start grazing your cover crop. The timing of grazing in relation to frost is an important consideration in post-wheat planted cover crops. The biggest concern is with plants in the sorghum family and the release of prussic acid after frost damages cell walls. A forage planted immediately after wheat harvest can provide 30 or more days of grazing before frost. In other cases, delaying grazing until after a hard frost may be easier, particularly when it may be time-consuming to move animals on and off the field and difficult to predict frost timing. Grazing should be suspended for 7 to 10 days after a frost to avoid prussic acid poisoning. For plants with prussic acid potential, delay grazing until plants achieve 18 to 24 inches of growth because prussic acid is highest in small plants or regrowth.

Determining Stocking Rates

Several key pieces of information are needed to estimate a stocking rate. The first is an estimate of the forage yield your field will produce during the period it will be grazed on a dry matter basis. How much forage will be consumed daily depends on animal body weight and forage quality. For green and growing forages, intake will run from 2.5 to 3% of body weight on a dry matter basis. Another key input is the percent utilization desired. In dryland systems, 30% is a conservative starting point unless it appears to be an excellent moisture year with above-average yields. Calculations can be made to estimate days of grazing for a given number of animals or the number of animals for a set grazing period. A Carrying Capacity Calculator is also available to help with these calculations. Example calculations to determine stocking rates are detailed in the full publication linked in the first paragraph of this article.

Example Timeline

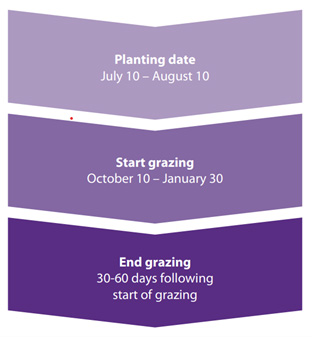

Below is an example timeline with suggested planting, start grazing, and end grazing dates for cover crops planted post-wheat. In good moisture years, grazing could occur in September and October. Depending on the species planted, livestock removal before the first hard freeze is recommended. Others may prefer to delay grazing until a week or more after the first killing frost.

Key Points

- Post-wheat plantings would include warm-season species such as millets, sorghum-sudangrass, forage sorghum, sudangrass, cowpea, lablab, sunhemp, or sunflowers.

- Planting a cover crop for forage could be grazed late summer through fall.

- Warm-season grasses tend to dominate over broadleaf species when planting cover crop mixtures.

- Cover crops must be planted immediately after wheat harvest to ensure crop establishment before the soil dries out following harvest.

- Yield variability is high when growing cover crops post-wheat under dryland conditions, ranging from under 1,000 lb/ac in dry years to almost 9,000 lb/ac in wet years.

- Stocking rates must be flexible because of the large year-to-year variability in cover crop productivity.

- Cover crops planted post-wheat can provide an average of 30 to 45 days of grazing, but the timing of grazing in relation to frost is an important consideration.

- Take caution for prussic acid and nitrates when growing summer cover crops for forage.

- Be aware of volunteer wheat growing in summer cover crops and manage accordingly for risk of disease and insect pressure carrying over to wheat planted this fall.

Sandy Johnson, Extension Beef Specialist, Northwest Research-Extension Center

sandyj@ksu.edu

Augustine Obour, Soil Scientist, Agricultural Research Center-Hays

aobour@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist, Southwest Research-Extension Center

jholman@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Extension Crops & Soils Specialist, Southwest Research-Extension Center

lsimon@ksu.edu

Tags: wheat fall forage cover crops forage