With most corn fields in Kansas already in reproductive stages (or close to flowering for late-planted fields), it is time to start assessing grain yield potential. Successful pollination is a critical aspect that farmers can evaluate by examining ear silks. Having conditions that favor the synchrony between the pollen shed by the tassels and the silks, the exposed silks should turn brown and easily separate from the ear when the husks are removed.

Corn flowering

The cool, wet early season, followed by a rapid onset of very warm temperatures, triggered a period of rapid growth for some corn fields in eastern and central Kansas. This unique set of environmental conditions sets the stage for potential pollination issues. In some fields, tassels remain tightly wrapped in the upper leaves and fail to shed pollen properly, causing pollination issues leading to poor or reduced kernel set. More about this phenomenon, with photos, can be found in a separate companion article in the eUpdate edition.

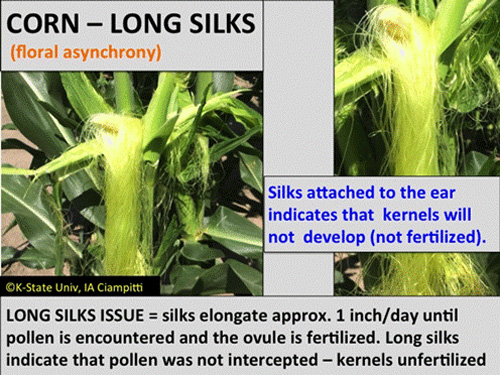

Another important point relates to the timing of heat and water stress. Water stress around flowering time (R1, http://www.bookstore.ksre.ksu.edu/pubs/MF3305.pdf) will negatively impact pollination due to a lack of synchrony between the pollen release and the emergence of the silks, which is a process that requires a lot of water. Heat stress around flowering will mainly impact the viability of the pollen. Usually, under dryland conditions in Kansas, water and heat stress happen together. Silks that have not been successfully pollinated will stay green, possibly growing several inches long (Figure 1). Unpollinated silks will also be connected securely to the ovaries (the undeveloped kernels) when the husks are removed.

Figure 1. Long silks primarily reflecting floral asynchrony. Silks that have not been successfully pollinated will stay green. Infographic by I. Ciampitti, K-State Research and Extension.

Corn yield potential estimation

Once pollination is complete or near completion, farmers could begin to estimate corn yield potential. To obtain a reasonable estimate, corn should be at least in the milk stage (R3). Corn can move quickly from silking to milk stage while only a limited portion of the state is in dough (R4), based on the USDA-NASS crop progress estimate of 11% in dough as of July 13. Before the milk stage, since grain abortion is still possible under stress conditions (mainly due to drought and/or heat stresses), it is difficult to tell which kernels will develop and which ones will abort.

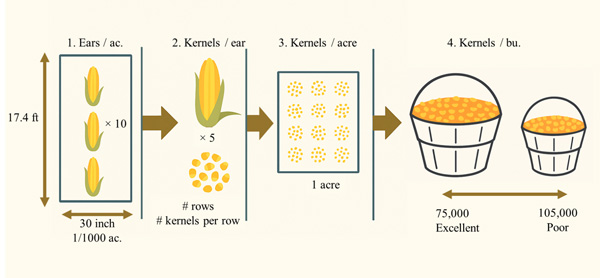

To estimate yields, we can use the yield component method (Figure 2). This approach uses a combination of known and projected yield components. It is considered “potential” yield because one of the critical yield components, kernel size, remains unknown until physiological maturity or black layer (R6). Therefore, we can only make an estimate of predicted yield based on expected conditions during the grain filling period (e.g., favorable, average, or poor).

Figure 2. Example of corn yield estimation under the “yield components method”. Graphic by Tina Sullivan, K-State Research and Extension.

Steps to estimating corn yield using yield components:

Step 1. Ears per acre via ear count in a known area, [Figure 2, step 1]

- With 30-inch rows, 17.4 feet of row = 1,000th of an acre. The number of ears in 17.4 feet of row x 1,000 = the number of ears per acre. Counting a longer row length is fine, just be sure to convert it to the correct portion of an acre when determining the number of ears per acre.

- Make ear counts in 10 to 15 representative parts of the field or management zones to get a good average estimate. The more ear counts you make (assuming they accurately represent the field or zone of interest), the more confidence you have in the yield estimate.

- Example: (25 + 24 + 25 + 21 + 24 + 26 + 23 + 21 + 25 + 23)/10 = 23.6 ears. Scaling up to an acre: 23.6 x 1,000 = 23,600 ears per acre.

Step 2. Kernels per ear, [Figure 2, step 2]

- There are two sub-components of kernels per ear: (i) the number of rows per ear and (ii) the number of kernels within each row. Most likely, the number of rows will be around 16, and ears always keep an even number of rows.

- The number of kernels per row depends on multiple factors, starting from the hybrid, but mainly on the growing conditions around flowering.

- To arrive at kernels per ear, multiply the two sub-components (number of rows x kernels per row).

- Note: Do not count aborted kernels or the kernels on the butt of the ear; count only kernels that are in complete rings around the ear. Do this for every 5th or 6th plant in each of your ear count areas. Avoid odd, non-representative ears.

- Counting 5 ears from each 17.4-foot area had an average of 16 rows and 27 kernels per row: 16 x 27 = 432 kernels per ear

Step 3. Kernels per acre = Ears per acre x kernels per ear, [Figure 2, step 3]

- 23,600 ears per acre x 432 kernels per ear = 10,195,000 kernels per acre

Step 4. Kernels per bushel, [Figure 2, step 4].

- This must be estimated until the plants reach physiological maturity.

- Common values range:

- Excellent: 75,000 to 80,000 for excellent

- Average:85,000 to 90,000

- Poor: 95,000 to 105,000

- At this point, the best you can do is estimate a range of potential yields depending on expectations for the rest of the season.

- Example: Under a scenario of temperatures above 100°F for the next 7-14 days and lack of rains (and if these conditions persist), it might be more than reasonable to assume below-average grain-filling conditions producing overall medium to small kernels. Based on the projected weather, a reasonable value might be 100,000 kernels per bushel. Note - this is just an example value for this scenario.

Step 5. Bushels per acre:

- 10,195,000 kernels per acre ÷ 100,000 kernels per bushel ~ 102 bushels per acre

Final considerations

If these estimates are close to correct, the example field used here is probably worth taking to grain harvest. Past experience indicates that this method of estimating yield usually provides somewhat optimistic estimates. Please consider these points when doing these field estimations.

Tina Sullivan, Northeast Area Agronomist

tsullivan@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Southwest Area Agronomist

lsimon@ksu.edu

Lucas Haag, Agronomist-in-Charge, Tribune

lhaag@ksu.edu