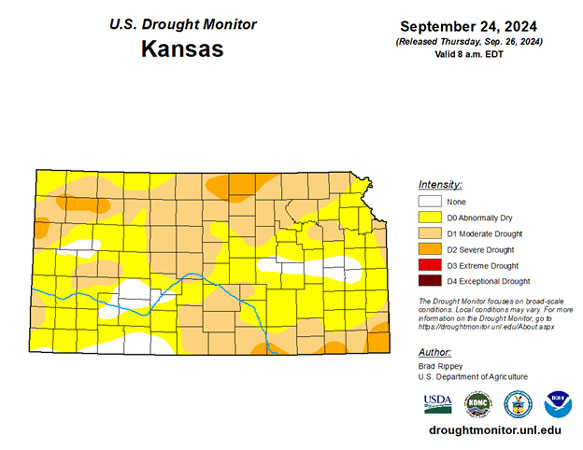

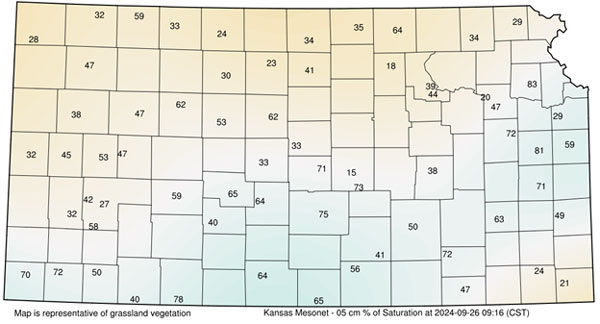

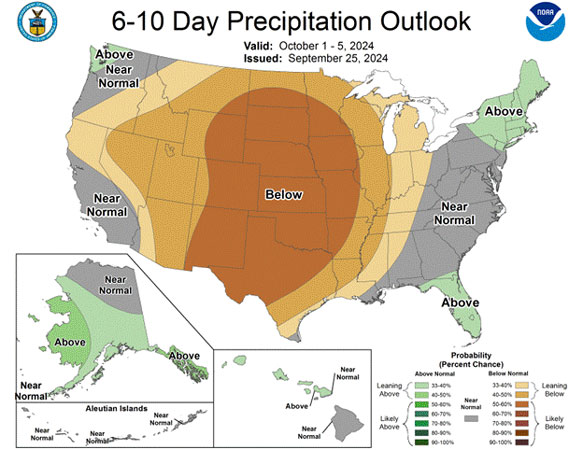

Despite some recent rainfall events, the most recent Drought Monitor shows 96% of Kansas still experiencing abnormally dry or worse conditions. (Figure 1). Topsoil conditions are getting drier in many areas of Kansas, particularly in northwest and north central Kansas (Figure 2). Unfortunately, the precipitation outlook is not very favorable (Figure 3). For wheat yet to be planted in these areas, producers are left with a few options.

Figure 1. Current drought conditions for Kansas as of September 24, 2024. Map from droughtmonitor.unl.edu.

Figure 2. Topsoil moisture conditions at 2 inches (5 cm) reported as % saturation at the 5cm depth on September 26, 2024. Map by Kansas Mesonet: https://mesonet.ksu.edu/agriculture/soilmoist.

Figure 3. The precipitation outlook was issued on September 25, 2024, for the next 6-10 days (Oct. 1-5). Source: CPC.

Option 1: “Dust in” the wheat

Producers can choose to “dust in” the wheat at the normal seeding depth and the recommended planting date and hope for rain (Figure 4). Some farmers may consider planting it shallower than normal, but this could actually increase the potential for winterkill, freeze damage, and poor crown development. Planting the wheat crop at the normal depth and hoping for rain is probably the best option where soils are very dry. The seed will remain viable in the soil until it gets enough moisture for germination.

Figure 4. Wheat dusted in near Belleville in October 2015. Photo by Romulo Lollato, K-State Research and Extension.

Before planting, producers should examine the long-term forecast and estimate how long the dry conditions will persist. The current short-term precipitation outlook (6 to 10-day) is leaning significantly toward below-normal rainfall (Figure 3).

Precipitation amounts are predicted to remain below normal for October. Should this occur, producers should treat the fields as if they were planting later than the optimum time, as the emergence date will be delayed. Rather than cutting back on seeding rates and fertilizer to save money on a lost cause, producers should increase seeding rates, consider using a fungicide seed treatment, and use a starter phosphorus fertilizer to improve early season development. However, producers should be cautious with in-furrow nitrogen or potassium fertilizers as these are salts and can make it more difficult for the seed/seedling to absorb water needed for germination. The idea is to ensure the wheat gets off to a good start and will have enough heads to have good yield potential, assuming it will eventually rain and the crop will emerge late. Wheat that emerges in October may still hold full yield potential, but wheat that emerges in November almost always has fewer fall tillers and, therefore, can have decreased yield potential.

Probably the worst-case scenario for wheat planted into dry soils would be if a light rain occurs and the seed gets just enough moisture to germinate but not enough for the seedlings to emerge through the soil or to survive very long if dry conditions return. Once the coleoptile extends to the soil surface, the plant must have enough moisture to continue growth; otherwise, it will perish. This situation may worsen if producers plant wheat following a summer crop such as corn, soybean, or sorghum, which depleted subsoil moisture through late summer. The wheat stand can be completely lost without subsoil moisture to sustain growth. If late October brings cooler temperatures, dusting wheat in becomes a more interesting option as soil moisture from a possible rainfall event could be stretched further.

Option 2: Plant deeper than usual into moisture

Planting deeper than usual can work if the variety to be planted has a long coleoptile and there is good soil moisture within reach. The advantage of this option is that the crop should come up and make a stand during the optimum time in the fall. If using a hoe drill, the ridges created could potentially keep the soil and emerging plants protected from wind erosion through the winter.

It’s possible that the wheat would get planted so deep that it would germinate but never emerge at all, especially if the coleoptile length is too short for the planting depth (Figure 5). Generally, it’s best to plant no deeper than 3 inches with most varieties in Kansas and the Great Plains. It is also important to remember that ridges formed by narrow press wheels can make the effective planting depth much deeper if the seed furrows fill in during a heavy rainfall event.

Figure 5. Deep-planted wheat can result in variable stands depending on if the coleoptile of the plants reaches the soil surface (plant on the left) or if it does not (plant on the right). In cases where the coleoptile does not reach the soil surface, chances are that the first true leaf will emerge below ground and perish with an accordion-like format. Photo by K-State Research and Extension.

Option 3. Wait for rain before planting

To overcome the risk of crusting or stand failure, producers may decide to wait until it has rained and soil moisture conditions are adequate before planting. Under the right conditions, this would result in good stands, assuming the producer uses a high seeding rate and a starter fertilizer, if appropriate. If it remains dry well past the optimum range of planting dates, the producer would then have the option of just keeping the wheat seed in the shed until next fall and planting spring crops next year instead.

The risk of this option is that the weather may turn rainy and stay wet later this fall, preventing the producer from planting the wheat, while those who dusted in their wheat could have a good stand. There is also the risk of leaving the soil unprotected from the wind through the winter until the spring crop is planted.

Crop insurance considerations and deadlines will play a role in these decisions. Another consideration is to delay the bulk of nitrogen application until topdress time in the spring, as wheat does not require much nitrogen in the fall. This would defer expenses until an acceptable wheat stand is assured.

Romulo Lollato, Wheat and Forages Specialist

lollato@ksu.edu

John Holman, Cropping Systems Agronomist

jholman@ksu.edu

Lucas Haag, Northwest Area Agronomist

lhaag@ksu.edu

Logan Simon, Southwest Area Agronomist

lsimon@ksu.edu

Christopher “Chip” Redmond, Kansas Mesonet

christopherredmond@ksu.edu