It is important to check sorghum and corn fields for stalk rot diseases before harvest. The two most common types of stalk rot in grain sorghum and corn are charcoal rot and Fusarium stalk rot. Both diseases survive in crop residue and can survive in the soil for many years. Stalk rots have somewhat similar symptoms, so it is useful to be able to tell them apart. Even in fields where lodging has not yet occurred, producers should be prepared to deal with stalk rot issues. This article focuses on stalk rots in sorghum, and a companion article in this eUpdate discusses stalk rots in corn.

Figure 1. Sorghum lodging caused by Fusarium stalk rot. Photo by Kim Larson, Agronomist.

Annual losses are difficult to determine because, unless lodging occurs, the disease mostly goes unnoticed. The best estimates are that at least 5% of the sorghum crop is lost each year to stalk rot. The incidence of stalk rot in individual fields may reach 90 to 100% with yield losses of 50%. The most obvious losses occur when plants lodge. More important may be the yield losses that go unnoticed. In sorghum, yield losses are caused by reduced head size, poor filling of grain, and early head lodging as plants mature early.

Symptoms generally appear several weeks after pollination when the plant appears to ripen prematurely. The leaves become dry, forming a grayish-green appearance similar to frost injury. The stalk usually dies a few weeks later. Diseased stalks can be easily crushed when squeezed between the thumb and finger and are more susceptible to lodging during wind or rainstorms. The most characteristic symptom of stalk rot is the shredding of the internal tissue in the lowest internodes of the stalk, which can be observed when the stalk is split. This shredded tissue may be tan-colored (Fusarium stalk rots), red or salmon (Fusarium and Gibberella stalk rots), or grayish-black (charcoal rot).

Table 1. Summary of stalk rots in grain sorghum.

|

Disease |

Symptoms |

Weather |

|

Charcoal rot stalk rot |

Internal shredding of lower nodes; black microsclerotia attached to the vascular tissue |

High soil temperatures ( >90 °F) and low soil moisture during grain fill |

|

Fusarium stalk rot |

Internal shredding of lower nodes; |

Dry conditions early and warm (82-86 °F) wet weather 2 to 3 weeks after pollination |

Charcoal rot

Hot, dry weather with soil temperatures in the range of 90 °F or more is ideal for the development of charcoal rot. Drought does not cause the problem, but it weakens the plants’ defenses. Charcoal rot is usually less severe if drought stress is not a factor.

While it is difficult to separate the effects of charcoal rot from simple drought stress, a good rule of thumb is that plants infected with charcoal rot will die about two weeks earlier from dry weather than plants that do not have charcoal rot. Grain fill that would have occurred during this period is the yield loss attributed to charcoal rot.

The plants will die prematurely. When stalks are split, the typical shredded appearance in the lower stalk associated with all stalk rots will be present. Additionally, there will be a gray to black discoloration of the inner stalk caused by numerous sclerotia (small, black survival structures of the fungus) forming on the vascular bundles and decaying tissue.

Figure 2. Close-up of charcoal rot in grain sorghum. Photo by Doug Jardine, K-State Research and Extension.

Fusarium stalk rot

Fusarium root and stalk rot are generally found in the same areas where charcoal rot develops. The pith of Fusarium stalk rot-infected plants will have a shredded appearance and is typically tan, but in some hybrids, the pith in the lower stalk may be pink to red. Plants may die prematurely or lodge.

Fusarium stalk rot is favored by wet conditions early in the season when denitrification or nitrogen loss from leaching. Research has shown that mid-season dry weather may predispose plants to later-season problems. Later in the season, following pollination, warm (82 to 86 °F), wet weather can leach remaining nutrients from the soil, resulting in late-season nitrogen stress and an increase in stalk rot.

Figure 3. Fusarium stalk rot in grain sorghum. Source: Stalk Rots of Corn and Sorghum, K-State publication L-741.

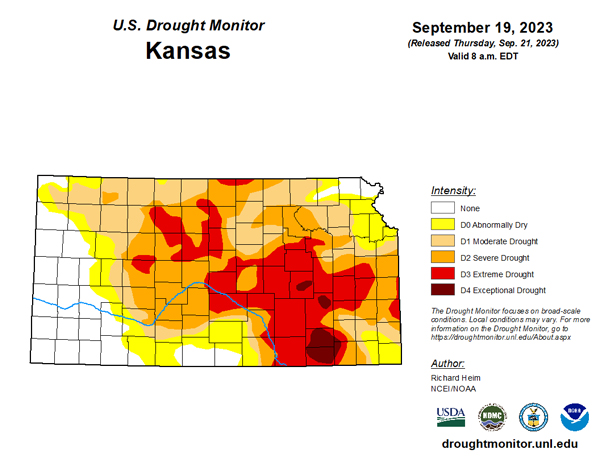

The most recent drought monitor index map for Kansas provides clues as to where stalk rot problems may occur (Figure 4). In the areas of the state currently under drought stress, charcoal rot may be more common. In other parts of the state with alternating wet and dry periods throughout the growing season, Fusarium stalk rot may be more common.

Figure 4. U.S. Drought Monitor Index map for Kansas as of September 19, 2023. https://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/

General considerations

Stalk rot is a stress-related disease. Any stress on a crop can increase both the incidence and severity of stalk rot. Research has indicated that when the carbohydrates used to fill the grain become unavailable due to nutrient shortage, drought stress, leaf damage from insects, hail, disease, or reduced sunlight, the plant uses nitrogen and carbohydrate reserves stored in the stalk to complete grain fill. When sugarcane aphid pressure is heavy, there will likely be an increase in the incidence of stalk rot, and producers should be prepared to harvest as soon as the grain is ready.

The loss of nitrogen and carbohydrate reserves resulting from leaf damage weakens stalk tissues and results in increased stalk rot susceptibility. Early maturing hybrids are generally more susceptible than full-season hybrids.

Besides irrigation or rain, little can be done to prevent stalk rot by late summer. No hybrid has complete immunity to the stalk rotting pathogens. When choosing a hybrid, a grower should select a hybrid that is not only a high yielder but has good standability and “stay-green” characteristics. This will help ensure that if stalk rot does occur, losses due to lodging will be minimal. A balanced nutrition program based on soil tests should be used. Overall fertility levels should be adjusted to fit the hybrid, plant population, soil type, environmental conditions, and management program. An excess, as well as a shortage of nitrogen, can lead to increased stalk rot problems.

Producers can check their sorghum for stalk rots by squeezing the lower stem with their thumb and fingers. If the stalks crush easily, they are probably infected with one of the stalk rot organisms and may lodge at any time. Check 100 plants across the field to determine the percentage of affected plants. If the percentage of stalk-rot-infected plants is high, sorghum should be harvested as soon as possible, even if it hasn’t dried down adequately in the field. If the stalks are firm, the plants will probably be able to stand just fine in the field for several more weeks if necessary.

Rotation with non-susceptible crops, such as small grains and alfalfa, will reduce the severity of stalk rot but will not eliminate it. A good insect control program is a must in limiting losses to stalk rot. In addition to the effect of leaf damage on stalk integrity, pathogens may enter stalks or roots through wounds created by insects. Hail damage will generally increase the amount of stalk rot damage.

For more information, see “Stalk Rots of Corn and Sorghum,” K-State publication L-741, at: http://www.plantpath.k-state.edu/extension/publications/L741.pdf

Rodrigo Onofre, Plant Pathologist

onofre@ksu.edu

Ignacio Ciampitti, Farming Systems

ciampitti@ksu.edu

Tags: sorghum grain sorghum lodging fusarium stalk rot charcoal rot stalk rots