While the summer statistics aren’t staggering, the impacts of above-normal temperatures and dry conditions have been substantial. As we move into fall, the focus turns towards harvesting and wheat planting. Copious moisture is needed to bring the state even close to normal. This story spotlights what is needed to erode moisture deficits and the fall forecast.

Precipitation Deficits

July’s statistics were greatly skewed by a cooler/wet period late month. Additionally, timely moisture has kept 2022 off the list of driest years on record thus far. August is making a run to change that though. As of this writing (August 24), only an average of 0.71 inches of precipitation has fallen statewide. If the month ended today, August 2022 would be the third driest August on record, behind only 2000 and 1913. Thankfully, moisture is in the forecast at the end the month.

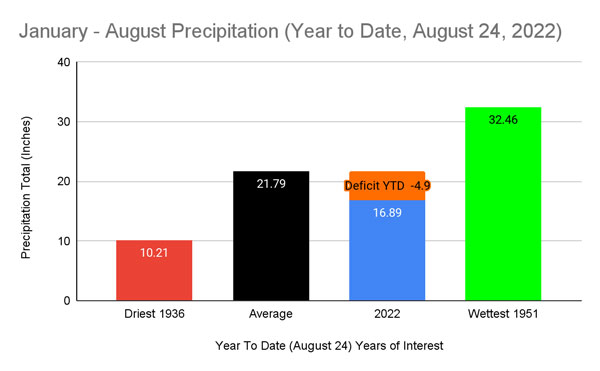

Thus far in 2022, the state has averaged 16.89 inches of moisture, 4.9 inches below the average value of 21.79 (Figure 1). This means that before the state could be considered normal for the year, 4.9 inches of precipitation would have to occur statewide. Keep in mind, eastern Kansas averages about twice the annual precipitation as in western portions of the state.

Figure 1. Year to date precipitation in 2022 compared to average, the driest (1936) and the wettest (1951). Departure from normal, -4.9 inches for 2022 is shown in orange as of August 24, 2022. Source: Weather Data Library

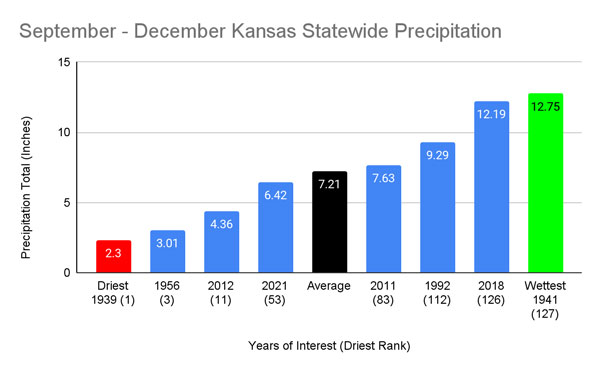

The bigger question then becomes how much can Kansas expect for the latter part of the year? The 30-year average moisture from September through December is 7.21 inches (Figure 2). Obviously, that isn’t uniformly spread across Kansas; one would expect about double that in the east and half that in the west. Additionally, September averages 2.52 inches, with decreasing amounts each month through the end of the year. December averages just 1.07 inches statewide. While heavy rains can’t be ruled out in the later months, it becomes more unlikely with time. Combined with the current deficit, Kansas would need 12.11 inches to break even for 2022. That is highly unlikely since there are only three September-to-December periods on record with more than 12 inches of rain. Note that despite the impressive dry conditions last November and December 2021 (Figure 2), moisture was near average due to the timing of the dryness and a substantial rain event in September and October. With the recent trends of heavy rain throughout the United States, let’s avoid a deluge that matches those numbers; that wouldn’t be beneficial. Slow and steady is our hope.

Figure 2. Statewide precipitation average through the remainder of the year (September through December) compared to some historic years of note. Source: Weather Data Library.

The Fall Outlook

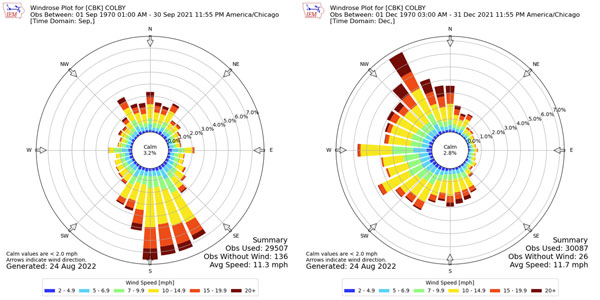

Typically transition seasons are challenging to forecast for and 2022 is no exception. With substantial drought persisting across Kansas and neighboring states, combined with the numbers above, drought will likely continue into 2023 barring an impressive pattern change. It is important to note the recent increases in moisture in both the southern Plains and the desert Southwest. These are areas to watch for potential positive feedbacks of increased moisture. Unfortunately, south/southwesterly flow periods are relatively rare as we begin to get frequent cold frontal passages later in fall with predominant north/northwest flow climatologically favored (Figure 3). Therefore, average air masses impacting Kansas become colder and relatively drier, not optimizing this newly increased surface moisture to our south/southwest.

Figure 3. Wind roses (showing wind speed and dominant average direction) from September (left) and December (right) at Colby. Source: IEM Mesonet.

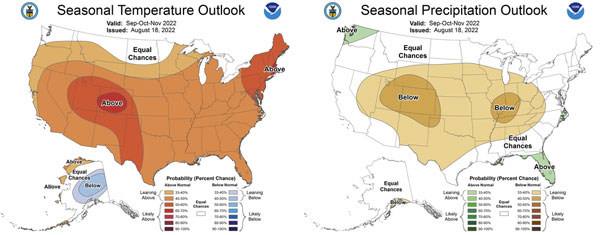

While other global and regional oscillations become more prominent during the winter months, the most dominant, the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), will likely be the main headline for winter 2022/2023. Forecasts predict the current dominant La Niña to persist for the third consecutive fall (and likely winter). 2021 remains in the front of our minds with the significant heat/dryness to end the year. These extremes are favored for Kansas winters during La Niña and are of great concern. While we aren’t forecasting extremes to that level, the current Climate Prediction Center (CPC) outlooks favor warmer/drier than normal conditions for the September through November timeframe (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Climate Prediction Center outlooks for Fall 2022. Source: CPC

There are a few additional glimmers of hope that remain. With persistent high pressure across the western US, similar to what brought significant rains to Oklahoma and Texas, stagnant moisture will reside in the southern Plains. With occasional frontal passages, this will present an opportunity for moisture to move northward in advance of each front. Several rounds of thunderstorms are possible as they interact with these fronts, more so should the fronts stall. This will hopefully bring some needed moisture for southern portions of the state. This pattern has been resistant to break down for almost two weeks and looks to hold on through at least mid-September.

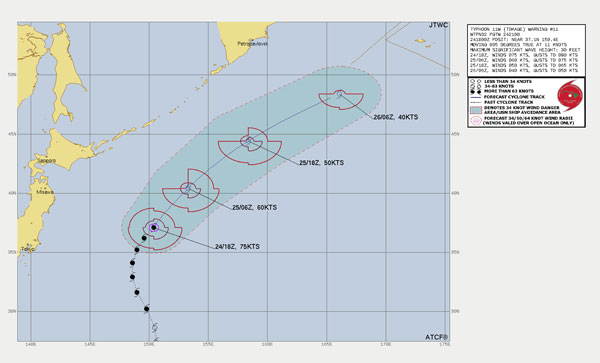

Lastly, while the tropics have been calm for the most part in the Northern Hemisphere, activity is beginning to increase. Our greatest focus resides in the western Pacific. A current typhoon named “Tokage” will turn northeast into the northern jet stream in the coming days (Figure 5). While this won’t have immediate impacts for the US, it will work to keep the current pattern in place across much of the continent for another few weeks. That may be well timed for that southern Gulf moisture to be transported slightly further north into Kansas as mentioned previously. The remainder of the season is expected to be near normal for the West Pacific and hopefully an additional storm next month (typhoon potential exists through November) could act to break down the pattern to an even wetter result. Unfortunately, forecast models are not confident on this solution and keep Kansas warm and dry for the most part. We need to hold on to the hope that this drought can’t (and won’t) last forever! However, it will continue into 2023.

Figure 5. Typhoon Tokage forecast track in the western Pacific (Japan to the left in the image). Source: Joint Typhoon Warning Center.

Christopher “Chip” Redmond - Kansas Mesonet Manager

christopherredmond@ksu.edu

Tags: winter weather fall outlook